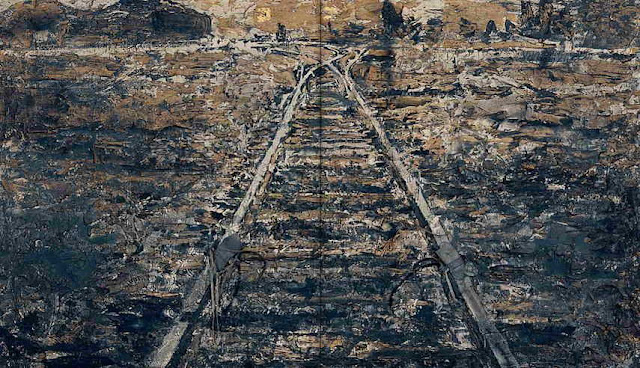

The Zone of Interest and Anselm - The Banality of Evil and the Battle Against Forgetting

In Jonathan Glazer's The Zone of Interest, the Holocaust is taking place literally over the garden walls. Auschwitz is Rudolf Höss's next door neighbor, but you wouldn't know it from the normality of routine his family goes through. His wife is happy with their lot (both their social status and the land they live on), the kids go to school, there are backyard parties, and he goes to the office each day to continue fine-tuning the extinction of Jews and other undesirables as dictated by his boss. He also ensures that quotas are met and later we find he's due to be moved in a promotion over all the camps.

This is how chillingly matter-of-fact Glazer's narrative is. If you remove the context, you would have a fairly typical and maybe even boring, domestic drama. You might even have some sympathy of both Höss and his wife and the disruption that a move might bring to the family. But their obliviousness to the very real evil that they are abetting and helping spread demonstrates the rot at their very hearts.

Every scene in the film is etched into one's mind, into one's heart. Christian Friedel as Höss and Sandra Hüller as his wife Hedwig are just an otherwise bland bourgeois couple. A couple of "good Germans", as Nietzsche might call them with all the acid he imbued that phrase with. Both actors fill these roles with as much humanity as possible and were this merely a domestic drama, they would certainly receive good notes for their performances. However, given the context, it's difficult to see their humanity.

You would be forgiven for thinking, well, she's not killing anyone, but only to the merest technicality of that term. Hedwig tries on the fur coat of a dead Jewess, their son examines teeth from victims at his father's work, Höss himself at a party in his honor idly muses what it would take to gas everyone there. The complicity in the extermination of six million Jews and an additional three million others extends horizontally across Germany (and their collaborators) and, I would argue, vertically through time down to the present day where we are witnessing a resurgence of dictators and demagogues and their mindless supporters.

Vertically through time down to today. We are still living with the Holocaust. After the war, the consensus was "never again", but the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have continued to paid witness to genocide, repeatedly. It plays out differently, but no less violently. It's as if, rather than be the massive tragedy that would bring humanity to its senses, the Final Solution was merely the first successful template for other humans to use in the mass slaughter of whole populations.

The danger of forgetting the Holocaust is co-equal and perhaps co-emergent, with simply ignoring its significance and using it as a prototype.

In some ways, Glazer's film seems to rest less on Martin Amis's novel than on another ur-text; Alain Resnais' Nuit et Bruillard/Night and Fog. Resnais masterpiece is a half hour of quietly brutal devastation, a documentary from Hell that ends with the question of who takes responsibility for the greatest single extermination carried out in history. Yes, yes, I'm aware that Mao and Stalin likely murdered more people overall, but their targets were predominantly their own people (along with other ethnicities, to be sure) - perceived or real political enemies, or sometimes just casual victims of famine that could have been averted in Mao's case. But genocide? The genocide that Mao is responsible for is that of the decades long erasure of the Tibetan people, their culture, and the sinicization of the Tibetan plateau. Even that pales in comparison to what the Nazis accomplished.

Resnais' work - written by Jean Cayrol, a Holocaust survivor - was commissioned and was a cri de couer from both director and writer that what happened should never be forgotten, let alone repeated. If there is a fault with Night and Fog, it's that it wasn't centered as a primarily Jewish tragedy. Even Resnais felt they missed the mark in attempting to universalizing it at the expense of missing the point that it was the Nazis' goal to firstly destroy the Jewish people. Nevertheless, the work stands and as the thirty or so minutes play out, as the images on the screen alternate between then-contemporary images of the camps in color and increasingly horrific documentary images from a scant ten years before, the enormity of Hitler's diabolical vision eats into the psyche.

Similarly, Glazer's work eats away at the viewer; you simply cannot escape the context. This second-rate functionary, this company man took pride in his work and was rewarded accordingly. His wife, speaking to a friend referred to losing a bid on a coat that belonged to a woman she used to do housework for. The woman was a writer it seems and when her companion asks what the woman wrote, Hedwig replies vaguely that it was "Bolshevik stuff, Jewish stuff."

In Resnais' film, the first scenes we see are of new vegetation growing over the land at Auschwitz; it is as if Earth herself wants to efface and overcome the evil that occurred on her surface. But the danger is that - were that to happen - memory would likewise grow dim, the Event paved over as with many of the remnants of Nazism in Germany today. Thus, Resnais and Cayrol strove to leave a document that would help to ensure the Holocaust wouldn't be sucked down humanity's collective memory hole.

Parenthetically, I don't believe either of them suspected that there would actually arise a significant number of denialists, who dare to hold - let alone, express - their doubt that the Holocaust ever took place. But they are but a symptom of the stupidity, ignorance, and hatred that caused it to happen in the first place.

By contrast, I would suggest that Glazer deviates from Resnais by showing us why and how the Holocaust cannot be forgotten; its memory is alive in the descendants of survivors and among all of us whose parents, grandparents, and other elders were alive at the time and who likely served in military to bring the Axis forces down. Its memory is also, I suspect, actually something that lurks deep down in the disturbed psyche of denier's unconscious, a sense of unease within their own darkness.

Franz Lustig's cinematography is stark; hard edges, vibrant colors and for sequences in which a young girl is seen stashing potatoes (I think) for prisoners who are working as slave labor around the camp, black and white negative exposure that renders the action a dreamlike antithesis to daylight madness and inhumanity that fills out the narrative.

Glazer, too, brings us back to the contemporary toward the end of the film. Höss has just had a physical, gets a clean bill of health, and we see him heading down the stairs. On the first landing, he stops and retches. Either end of the hallway is a void of shadow. The scene cuts to two women opening up the Auschwitz memorial museum to begin their rounds cleaning before opening.

As casually as Glazer has let this horror story unfold, the aftermath is likewise shown just as casually; we see a woman cleaning one of the mining cars used to deliver corpses to the furnaces, a mounted exhibit of the striped uniforms inmates - victims really, please let's call them what they were - wore, and the piles of shoes behind a glass being cleaned by another woman. In the background, we hear a vacuum cleaner, which by this point, is one of the most soothing sounds in the entire film.

Indeed, the sound design in The Zone of Interest is paramount to the film's power; we hear the ever-present rumble of the furnaces and the occasional cries of someone who is being punished, tortured or murdered, but so muted that it almost doesn't register, but when it does, good luck in holding back your sorrow, your tears.

To be clear, as well, "zone of interest" is a literal translation of "Interessengebiet", a term used for the restricted area around Auschwitz. In the context of the film, we are in that area - our interest is very much locked on the proceedings. We cannot turn away.

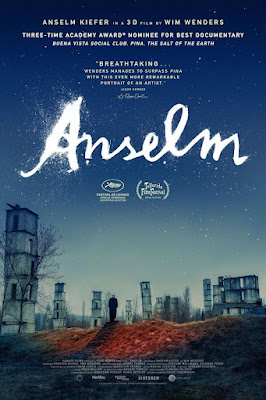

If Glazer's film is one of the perfect depictions of the quotidian realities of mass murderers's lives and the effects of their work on the rest of the world, Wim Wenders' portrait of Anselm Kiefer is no less urgent in its assessment of how Germany's (specifically and for reasons to become clears shortly) younger generations may successively forget the Holocaust and how his work and provocations served and continue to serve keeping it at the forefront of his art.

Kiefer's early work - both plastic and performative - were met with resistance from the art world in Germany. They accused him of being the very thing he wasn't; a fascist. That said, in an interview when asked why he doesn't call himself an anti-fascist, he replies by saying that the real anti-fascists were the ones who fought the fascists in the war.

Much of Kiefer's projects focus on the understanding that his generation and those that follow are not the ones who ended the Nazi regime and their responsibility is to not let it happen again but as importantly, to not forget that it happened. It is extremely important to bear in mind that Kiefer studied under Joseph Beuys, likely the first artist in Germany to confront the Holocaust in art and who realized that given the government's official paving over (literally and figuratively) of the era would only serve to erase it, an art would need to exist that could both keep history from being pushed down into forgetting and promote healing by acknowledging what had happened.

Beuys had joined the Luftwaffe at 21. He had a kind of conversion after being shot down, at which point he told the myth that he had been found by Tatar tribes people who nursed him back to healthy using fat and felt, two materials he would later use in his work. The story didn't happen; but it did work in leading credence to Beuys's methods as an artistic shaman.

Twenty-four years younger and very talented himself, Anselm Kiefer absorbed Beuys' lessons and repurposed and redirected his work to be even more confrontational. There is a documented performance piece of Kiefer photographing himself at different locales around Europe giving the Nazi salute. The salute was - and I believe, still is - illegal in Germany; but Kiefer's explanation to an interviewer that he was occupying all these places fulfills the intent to demonstrate the terrifying spectre of Nazism that "occupied" all these places within the span of the previous generation.

While Kiefer was reviled more than lauded in his home country, he was very well-received outside of Germany. His works are often of massive scale and his two ateliers over the years take up several acres. We see him biking around a warehouse full of his work and supplies. Imagine a Wal-Mart of a man's art and you have some idea of the scope of what we encounter throughout the film.

|

| The towers on fire. At a glance, they could be mistaken for smokestacks. |

The works are myriad - goddesses of Greek mythology as echoes of Winged Nike of Samothrace stand in wedding gowns, headless abstractions powerful in their godhood but opaque to modern eyes, divorced from the spirit that brought them into the human realm millenia ago; huge towers of lopsided/off-center buildings stand like branchless trees populating an architectural forest; landscapes forged by fire - literally - as various materials are affixed to surfaces the size of a wall are set aflame, extinguished and the charred matter used as a literal burnt sienna or pitch black.

Each of these varieties of work call to mind the camps and the complicity. Anselm Kiefer may not be shy, but he has every reason for being forthright and outspoken; any nobility Germany had before the rise of National Socialism was lopped off at the neck. Those towers of buildings might well reflect the instability and fragility of the world we're in and the collapsing memory of humanity and history. As for the landscapes, I'll leave a picture of one below next to one a photograph used in Night and Fog.

Wenders' film is an extension of his subject's project; as much as the camps still stand and as much as memorials abound, the significance of what they stand for can be lessened by apathy, by ignorance, as much as by vocal and/or physical acts of bigotry and hatred.

Shot in 3-D, my first thought was this is a brilliant way to view work by an artist in a documentary, particularly sculpture and three-dimensional works. But then, something else sank in; by extension, as well, we are brought into the milieu that the artist is attempting to keep alive, keep before the collective, the audience, those that might begin the work of forgetting.

These two films serve as twins. One is a more or less fictional narrative and the other a documentary with narrative flourishes (we see actors playing a younger Anselm Kiefer at different points in his life); but both are rooted in the worst mass murder in history. They are both examinations of the effects of that event.

The Zone of Interest itself and Anselm Kiefer's art are both effects of the Holocaust. That the first movie is the work of English, Polish, and German collaboration is itself heartening; that Wenders and Kiefer made their film is likewise a sign of hope and possibly carries further part of the process of healing without forgetting.

There's a difference between genuine healing and just putting a bandaid on a deep wound. Properly treated, it can scar over; superficially covered over, it may fester and corrupt more deeply the underlying tissue. It won't be forgotten, but it will continue to make the subject ill. Repress a memory, the trauma of the event will arise in other ways, possibly worse than before. Works like these go some way to healing and possibly, prevention.

|

| A still from Night and Fog. |

|

| "Eisen-Steig" by Anselm Kiefer - 1986. |

Comments

Post a Comment