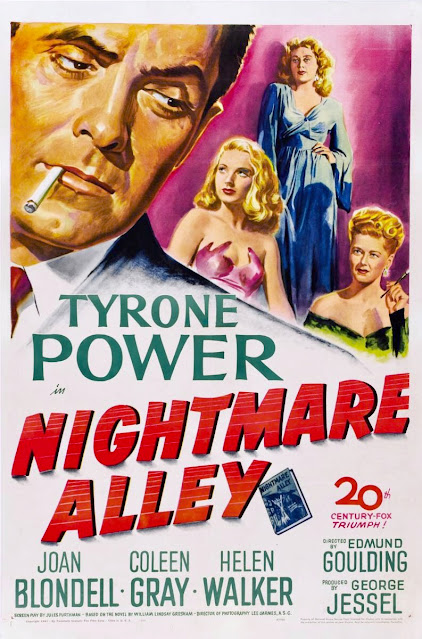

“Nightmare Alley”: Part One (1947)

Ahead of the release of Guillermo Del Toro’s remake of “Nightmare Alley”, I took it upon myself to rewatch this gem after nearly a half century since catching a glimpse on TV. Much of it (most) went over my head but it was permeated with enough despair - too much - to miss. Watching it with fresh eyes, I’m astonished that I’ve not seen it in subsequent years and frankly, just plain astonished.

I disagree with the assessment that it’s not a classic and to some degree with James Agee that it’s “intelligent trash” (it is, but it’s not that exclusively). It’s unsettling in its lead amorality and the gray areas he inhabits. This is to say nothing of others in the film and in and of themselves would be almost characters were it not for a smarter than the material demands script and intense performances all around.

It opened to mixed reviews in 1947 and failed at the box office but it proved that Tyrone Power was much more than heir to Errol Flynn’s swashbucklery. Actually, he had proved that with the previous year’s “The Razor’s Edge”, also directed by Edmund Goulding who directed “Nightmare Alley”.

On the surface, there’s not a lot of plot: Stanton (Stan) Carlisle is a mentalist in a carny who ascends to recognition in Chicago nightclubs and after a con goes wrong, finds himself back in the carny as a geek. From that description, we could be very well on our way into Tod Browning territory but there’s so much more.

Zeena: “You like this racket, don’t you?”

Stan: “Oh, lady, I was made for it…”

Stan works with Zeena and Pete, two former giants in the mentalist trade but who fell on hard times when Zeena began having affairs with other men and Pete began to self-medicate with booze in a bad way. Molly, a young showgirl tells Stan about Zeena and Pete’s back story and how before he hit the bottle, they had a code worked out so that Pete didn’t have to be on stage with her; he would read written questions to her from the audience and via inflection and code words, she could work out what the questions were and answer accordingly.

One night, Stan mistakenly hands Pete wood grain alcohol instead of the grain alcohol he had just bought for himself and Pete dies, leaving Zeena to accept Stan as a full partner and employ the code approach again. Stan had been romancing Zeena along the way and patently and unceremoniously dumps her for Molly and Stan and Molly (sounds like a comedy duo I know of) are wed under duress when the carnival folk turn on them. Stan sees this as an opportunity to take the show to the clubs in Chicago with Molly as his partner and before long he encounters Lilith Ritter, a sketch psychotherapist who provides Stan an entree into the upper echelons of Chicago society.

At this point, Stan is introducing visions of the afterlife into the act and conning people as a medium. With the promise of a large payoff and a media empire, Stan cajoles Molly into assuming the appearance of the deceased lover of a wealthy Chicagoan. When she can’t go through with the performance, Stan’s duplicity is revealed and he realizes that flight makes right. He meets up with Lilith who hands him an envelope full of money and who convinces him to go but wait until things calm down before returning. He is en route in a cab to meet Molly at a train in the suburbs but upon discovering he’s been duped, he returns to Lilith who lets him know that she’s got the goods on him should he try to threaten her. It’s a masterful turn and Stan catches up to Molly to put her on the train while he journeys forth to follow his fate, such as it is.

Like Pete, he hits the bottle hard and wends his way back to a carny where the only job he’s offered is that of a geek until they can hire a real geek (what could be more insulting and degrading? You’re not even a real geek!) The same night he’s hired, Stan has an episode and is running round assaulting his co-workers. Turns out Molly is working at the same carnival and is able to approach Stan and calm him. The movie ends with the carnival manager and others now aware this was once “The Great Stanton”, asking what happened to him. “He reached too high….”

None of this could be sustained without a cast and crew who could breathe something into it and while the New York Times recognized the intensity of performance, they dismissed it as too much so for entertainment. Hell, Daryl Zanuck found the film too disturbing and ordered cuts to it (apparently, missing from modern prints is a sequence with a geek early on in close-up screaming with a blood smeared face).

Stan: “You’ve got a heart as big…”

Zeena: “Sure, as big a as an artichoke, a leaf for everyone.”

As it is, the film remains disturbing because of the overwhelming sense of despair in a dead-end life of conning the marks. Stan’s hubris at being the smartest guy in the room is sheer toxicity oozing from the screen. By contrast, everyone else is drawn with harsh outlines hinting at troubled pasts of trauma and existential terminal blues. Joan Blondell’s Zeena is a woman with a wild past now atoning for what she put her husband through and Ian Keith’s Pete is about as close to living on fumes dead as I’ve seen in quite some time. He’s remarkable when he comes to life before he finally drinks himself to death and you sense the depth of his attachment to Zeena. Similarly, Blondell’s best work is in the way she looks at Pete and Stan. With Pete, there’s a mix of genuine pity, ruefulness and concern. With Stan, you sense she’s still keeping him at a remove. She’s not an idiot and rightly doesn’t trust him completely.

Molly to Stan: “Wait a minute, mister. You’re not talking to one of your chumps. You’re talking to your wife! You’re talking to somebody who knows you red, white, and blue. And you can’t fool me anymore.”

Stan to Molly: “Listen to me, I’m no good. I never pretended to be. But I love you. I’m a hustler. I’ve always been one. But, I love you. I may be the thief of the world, but with you I’ve always been on the level.”

Colleen Gray as Molly is genuine goodness and supports Stan up until he tells her of his plan to get the millionaire Ezra Grindle (Taylor Holmes) to part with a substantial sum of money/fund his projects if he can only see his long gone beloved. The discussion they have revolves very much around how Stan is “going against God.” Stan takes umbrage to that and avers that he’s never used God in any of his cons; sure, he tells people what they want to hear and even tries to convince Molly that he’s doing these people good (though Power nails the hollowness of Stan’s utterance so well you can tell Stan doesn’t believe it himself). In any case, Molly acquiesces and all is well until the moment when Grindle gets on his knees and begs forgiveness for being a shitty human being after her (well, his lover’s) death.

Gray brings a stunning range of emotions to play in a different range from what she brought to her character in “Red River” but perhaps not too far afield from her role in Kubrick’s “The Killing” a number of years later.

Helen Walker as Lilith Ritter is a study in surgical technique. Crikey, she was scary good as she played Stan like Nero’s fiddle. Seriously, she oozed so much confidence and sway over him I thought the film was going to take a whole other turn when they met on the docks plotting next moves. When Stan hands Lilith a hundred and fifty thousand dollars cash and trusts her to stash it, I was shaking my head at how much of a sap this guy is. Later, when he threatens her, she shuts him down so thoroughly, you almost feel sorry for him. But like the best fops and failures in noir, Stan is doomed by his own actions.

And it’s this last point that makes this such a compelling example of the genre. No one gets shot, there’s no real violence to speak of, but the lives lived are all in the shadows, the setting feels as much twilit as in a dream even though the black and white is in stark contrast throughout. In many ways, we don’t leave the carnival of souls even when we follow Stan and Molly into the larger world. He’s far too into the life to ever get out of it and Molly, bless her; for her, the carnival is family.

But Stan is the only character whose agency is so monomaniacal that he can’t see people as only means to an end, for the most part. I do sense that he might care for Zeena and Molly, but Lilith sums him up when she says, he’s perfectly normal after he’s come to her to share his feelings of guilt about his unwitting part in Pete’s death. She states plainly that he’s essentially good at heart but takes advantage of people when he thinks it will improve his lot. This is a sure sign that she’s way ahead of him in the game of life, and it almost sounds like she’s giving him a key to figure himself out. But he doesn’t. He continues down his path of wreckage and does so with abandon, though Stan would no doubt argue that no, it’s all planned out.

The talent behind the camera is huge in the way that many quiet greats are. Jules Furthman who adapted William Lindsay Gresham’s novel was also responsible for the scripts of several Von Sternberg movies (“Blonde Venus”, “Shanghai Express”, and “Morocco”, among others), “Mutiny on the Bounty”, “The Outlaw”, “To Have and Have Not”, and “The Big Sleep.” I could go on which hints at the quality of what we’re dealing with.

Edmund Goulding’s career - like Furthman’s - began in the silent era, but a smattering of his work in sound is revelatory and he will always have a special place in my heart for directing “A Night at the Opera”. Of course, “Grand Hotel”, “The Dawn Patrol”, “Dark Victory”, and “Of Human Bondage” aren’t too shabby. He is tied with Jack Conway for having directed the most Best Picture nominees without having ever won a nomination for Best Director. No one ever accused the Academy of knowing what it’s doing.

To round out the embarrassment of riches, we need to look at both the editor and the DP.

Barbara McLean was one of the most nominated editors of the 30s and 40s. She won for 1944’s “Wilson” but had been nominated for “Les Miserables” and “The Song of Bernadette” prior to that. Her last nomination was for “All About Eve” but to look over her filmography is nuts. It’s a well-known fact that as opportunities for women as studio heads, producers, and directors dried up, those who stayed in the business often turned to editing bays. The plethora of riches that these women possessed is only now being acknowledged and I recommend checking out Barbara’s IMDb page to find out more.

Finally, Lee Garmes’ cinematography is one more feather in this flick’s cap. Like Furthman, there’s very much a Von Sternberg connection (Garmes took home the statue for “Shanghai Express”). His career began in 1916 and continued well into the 70s. He was an early proponent of shooting on video and much of his work is characterized by deep shadows and depth of field. He didn’t showboat a lot because he didn’t need to. His compositions tell you all you need to know about the characters in the frame and this particularly clear here.

“Nightmare Alley” is a remarkable artifact and I see why Del Toro wants to shoot his version. I’ll be curious to see what he does with the psychological aspects of the characters and what he does with the plot. Carnivals by their nature are somewhat disturbing (aside from geeks and Lost Souls). I think of John Merrick’s torture as a sideshow freak in Lynch’s “The Elephant Man” and the extremely troubling “Freaks” from Browning.

“You know what a geek is, don’t you?”

Stanton Carlisle replies, “Yeah. Sure, I… I know what a geek is.”

“Do you think you can handle it?”

“Mister, I was made for it.”

Let that shudder you may have just felt give you an idea of what this film is like.

|

| James Flavin in early establishing shot. |

|

| Colleen Gray as Molly |

|

| Colleen Gray as Molly and Tyrone Power as Stanton |

|

| Helen Walker as Lilith Ritter |

Comments

Post a Comment