Cronenberg’s First Four: On the Way to the New Flesh

“That a film might fail internally because it’s not well-conceived or well-crafted, that’s possible. Obviously my early films, as I’ve said many times, were my film school. You’re seeing me learn to make films right before your very eyes, and obviously the early films are, y’know, they’re pretty rough… but vulnerable? This is the thing that young filmmakers and young artists out there of any kind are shocked to discover. It’s all vulnerability. You are putting yourself out there for anyone to comment on, and to react to, in ways that might surprise you. I’m totally vulnerable, with every film. But not necessarily because I’ve made a bad film or I’ve done something I didn’t know I was doing, but because you are offering yourself up for evaluation.”(1)

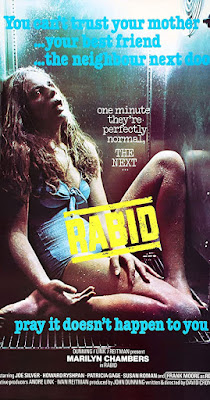

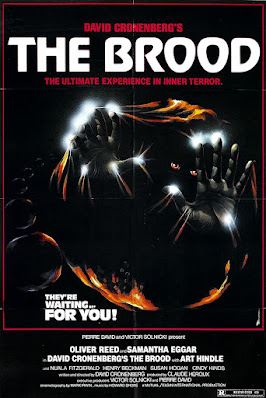

The first film of David Cronenberg’s I saw was “Videodrome”; it was riveting and provocative, both viscerally and intellectually and I couldn’t say that it was more one than the other. I’d heard about “Scanners” but most of what reached me made it sound like a stupid, if not silly, B-movie with exploding heads. When I learned that it was by the same filmmaker, I had to rethink a few things. Later, I heard people babble about “Rabid” and how it wasn’t very good, so I didn’t feel terribly obligated to seek it out. “Shivers” aka “They Came From Within”? I kept getting it confused with James Gunn’s “Slither” and really didn’t know enough about the film to care. “The Brood” was often dismissed as being misogynist and an unworthy entry in his filmography.

But I did love most of Cronenberg’s oeuvre from “Videodrome” on and if I didn’t love a particular work, there were still enough ideas and expert execution that I knew I’d still come away challenged, if not satisfied.

Recently, I did myself a favor and watched all four of the pre-“Videodrome” movies mentioned. What I set myself as a task was to see these early films as complete works on their own and where they stand in relation to the later works but mostly, how they inform or act as seeds for Cronenberg’s journeys as a director. I stress the plural because Cronenberg is as multiform a filmmaker as any in the history of film.

As William Beard pointed out years ago, Cronenberg has provided extensive fodder for scholars of critical film theory and cultural criticism in general. I argue that his thematic content and approach didn’t just lay the groundwork for later/“greater” works; it was there from the beginning. As much as David Lynch, possibly the only other contemporary filmmaker to whom Cronenberg can be matched, though one whose work is more opaque, the early works show a sure command of the medium and what the filmmaker was saying.

Aside from “The Brood”, I don’t think any biographical elements explicitly inform his films. To be sure, any given work is probably related to an author’s life by intention, focus, etc., but I really don’t think that in this case (or for that matter, in a number of filmmaker’s), biographical information is helpful or necessary. There may be some late seventies’ Canadianisms I might miss, but for the most part, these four works present themselves as almost complete on the surface.

That does not mean they are superficial. Far from it, as I think we’ll see.

Before we get too far into the films themselves, I have to say that generally speaking, they are by turns disturbing, funny, and heart-wrenching. That last is something most tend to associate with the tragedy of Seth Brundle in “The Fly”, but again, it does a disservice to Cronenberg to see him only or primarily as a poet of body horror. If that were the case, then his work wouldn’t be nearly as compelling.

If anything, he may be one of the most humanistic of directors. His arc over the past thirty-five years trends to increasing engagement with how we live our lives of the mind and if there are still riveting or extreme sequences here and there, they exist to support a deeper inquiry into human existence (or eXistenZ).

Also, it’s unnerving how prophetic these films feel in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the increase in trends across the U.S. and the world toward right wing or more fundamentalist/populist regimes. The conflicts between power holders in these films and the individuals who discover or resist them carry an additional charge. In some cases, the revelation that it is the powerful who least understand the results of their actions lands with greater emphasis than expected.(2)

Prologue: looking in Cronenberg’s shorts and two featurettes

Often juvenilia is dismissed as, at best, works of curiosity and for completists; but also, just as often, they are revealing of an artist’s preoccupations and themes that will be a throughline through works across a lifetime. Both “Transfer” (1966) and “From the Drain” (1966) are quick takes on psychiatric technique, patient to analyst transference, and the utter gobbledygook of jargon that contravenes anything like genuine understanding until finally someone just comes out and speaks plainly. Oh, and in “From the Drain”, at least, we see the first hint of Cronenbergian “body horror” in the form of tendrils that rise from the drain of the bathtub the two protagonists are sitting in.

Right. The bathtub. The settings in both shorts are minimal and speak somewhat to Beckett. Open spaces in the Toronto winter in “Transfer” and the aforementioned bathtub for “From the Drain.” Neither is particularly plot driven and/but both are fairly sardonic and satiric in their dialog. Yes, they are for the most part, merely curiosities, but they do hint at what’s to come.

“Stereo” (1966) and “Crimes of the Future” (1967) are more fully formed. “Stereo” draws on the theme of biologically engineered telepathy and its implications, somewhat presaging “Scanners” but already investigating corporate or at least, institutional development of quasi-weaponization of the paranormal. I say “quasi-“ because much of the narrative is more focused on what happens when a group of telepaths are brought together and how they relate or fail to and what results. There is also the thread running through it of the researcher who becomes involved with his subjects and an interrogation of what happens to the ideas of gender and sexuality if minds meld together into a kind of polymorphously perverse union. It is a curious bit of filmmaking and photographically light-years beyond the shorter works.

Both featurettes’ plots unspool in voiceover because the camera Cronenberg used to shoot the films made too much noise. Nevertheless, “Stereo” boasts some glorious compositions and rich black and white cinematography. It is also the first instance of Cronenberg’s use of architecture as both setting and character. The brutalist architecture is great for Constructivist and Bauhaus styled compositions and also as a participant of the distance between people who, paradoxically, are supposed to be in such deep communication with one another.

“Stereo” has its satire in the remarkably convoluted, philosophical hermeneutics-laden voiceover; but it also engages the alienation and anxieties of human existence, especially when presented with the potential to have no “true” self and the development of secondary selves that are partitioned to protect that diminishing “true” one. The horror is very much implied here. The film, like the research it purports to detail, peters out, but it is an intriguing if not compelling ride.

“Crimes of the Future” has a broader canvas and a multithreaded plot. The satire is more biting and the film moves us closer to Cronenberg’s distrust of institutional malfeasance and its unintended (and uncaring) consequences. Briefly, we follow the narration of Adrian Tripod - a follower/student of or assistant to the great Antoine Rouge, a mad dermatologist whose cosmetics resulted in the death of much of the female population. The men left behind are sexually ambiguous and unsurprisingly weird.

In the wake of Rouge’s disappearance and the demise of the female population, men are afflicted with foamy discharges and chocolate-colored hemorrhaging before they die. Apparently, the discharges are tasty and possibly hallucinogenic. Additionally, Tripod is a member of a subversive organization of pederasts whose aim is never quite explicated, though it involves a five-year-old girl who has matured to 30 years of age while remaining in the body of a child. Nothing explicit occurs, but there is sequence of the camera fixated on the girl as she stares into the lens like a subject from Balthus painting. Again, Cronenberg’s eye for framing the disturbing aesthetically is itself shocking. Nothing happens and yet, you know it has.

“Crimes of the Future” has it over “Stereo” structurally and narratively. In the year between, Cronenberg’s work is more focused, and he allows for more space his story for events to play out. The narration is still parodistic; but the film has greater heart.

There is another symptom whereby some men’s bodies grow organs outside the body. They are not tumors or growths, but genuine organs with unspecified or perhaps latent, functions. The idea that humanity or what’s left of it, is mutating into something else foregrounds what is to come in his features. Brian O’Blivion’s interpretation of his cancer in “Videodrome” (“I believe that the growth in my head-this head-this one right here. I think that it is not really a tumor... not an uncontrolled, undirected little bubbling pot of flesh... but that it is in fact a new organ... a new part of the brain.“) comes to mind. The body betrays the self and becomes a thing unforeseen.

Those First Four Features

“Shivers” (1975)

“Roger, I had a very disturbing dream last night. In this dream I found myself making love to a strange man. Only I’m having trouble you see, because he’s old… and dying… and he smells bad, and I find him repulsive. But then he tells me that everything is erotic, that everything is sexual. You know what I mean? He tells me that even old flesh is erotic flesh. That disease is the love of two alien kinds of creatures for each other. That even dying is an act of eroticism. That talking is sexual. That breathing is sexual. That even to physically exist is sexual. And I believe him, and we make love beautifully.“

“Hungry... Hungry for love. I'M HUNGRY FOR LOVE!”

While acknowledging that “Stereo” and “Crimes of the Future” are indicators of what is to come, I can’t say for sure that “Shivers” represents Cronenberg’s turn to the “mainstream”. Certainly, on its surface, it’s an engrossing sci-fi B-movie. But what a lousy description that is.

While there is a certain amount of DNA shared (and yes, I’m carefully choosing my words here) with 1956’s “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” and George Romero’s “Night of the Living Dead” (1969), the hermetic setting of the high-rise condo building “Starliner Towers” presages J.G. Ballard’s “High Rise”.

The central driver of the plot is the development of parasites, results of “a combination of aphrodisiac and venereal disease” (this is a direct callback to “Stereo” and “Crimes of the Future”) by one Dr. Emil Hobbes (Fred Doederlein). If this sounds unreasonable, consider that his motive was to find a way to overcome humanity’s increasing living in our heads and separation from our bodies. Already, Cronenberg is setting the stage for an assault on normative values. The parasites were originally supposed to substitute ill or failing organs and then, and I’m not sure how, become motivators for, well, extreme desire (politely) or turning their hosts in stark-raving (and violent) sex maniacs.

Hobbes’ experimental patient resides at the Towers and she, in turn, transmits the parasites throughout the community. Recounting each infection would expand this essay to a small book, but each time a new person or group contract the parasites, the mayhem that ensues is rampant randiness, if not outright, well, rape. If there’s an even more disturbing element in this, it’s that the parasites turn their host into predators. What adds to the uneasiness of watching this, is that given the preposterousness of the premise, the execution is actually kind of funny. Until it’s not.

Increasingly, as more of the Starliner Towers is consumed by sex and violence, the more horrific the overarching conceit becomes. It’s with this element that Cronenberg’s opus is already more transgressive (a term that is and will be used repeatedly throughout to describe his work, particularly the ones under discussion) than, say, either Romero’s or Don Siegel’s works. If anything, as social commentary, “Shivers” is a more multilevel critique than “Night of the Living Dead” or “Invasion of the Body Snatchers”; it is remarkable not just how much is packed into the film thematically, but how efficiently the various elements are compressed.

It would be naive to overlook the interrogation of masculine roles and by extension patriarchy, the critique of unrestrained sexual commodification, and the examination of a hyperfocus on societal sexualization, in general. Folded into these, we are also faced with scientific amorality left to its own means sans concern for consequences where often the consequences have a decidedly negative impact on a population. I suspect, too, that there is a subtle critique of classism, insofar, that the tenants of the high rise are living in a desirable community removed from the city and one assumes, considered “exclusive” (“Explore our island paradise, secure in the knowledge that it belongs to you and your fellow passengers alone”). Thus, there’s the idea of what happens when the economically privileged succumb to unchecked desires (unlimited consumption that continues to only amplify itself in the quest for “more”).

But back to sex and violence. Much of it is all right there in the parasites themselves, little red phalloi with open orifices for sucking and burrowing into their hosts. The sound design is spot-on here when they latch onto flesh or viscera. They replicate in the abdomen and are mostly passed orally. Oh, and they can launch themselves into the air like leaping leeches. I’m writing this description with a degree of lightness, but honestly, the flip side of the parasites is that in execution, they are pretty ghastly. They scar the flesh, vomit out of mouths, and in one instance, slither up a bathtub drain to crawl into the great Barbara Steele’s vagina. They are literally transgressive. No metaphor required.

With the parasites Cronenberg’s use of body horror as image, plot device, and metaphor begins in earnest. The parasites exemplify the erasure of the body or flesh as boundary. They remove the safety and certainty of being safe or comfortable within one’s skin. That they are phallic by design conjures up both the insertive and the excretive.

That they consume and subsume the individual and by ex-/intention, identity, results in a kind of eradication of interiority. There is an ontological erasure that obtains when the host is invaded by and/or excretes/shares a parasite. One ceases to be who or what one was. One ceases to be. This isn’t so removed from those other movies mentioned as precedents to this one; but where the zombies and aliens are also representatives of or metaphors for similar erasures, in “Shivers”, the use of the body as a visual analog to erasure via a transgressed/subjugated sexuality is frighteningly more intimate.

What separates “Shivers” from previous and similar films is that the absorption of identity takes place as the result of sex-as-disease (or even death) and the origin of that being the result of medical discovery where the result was unforeseen and uncontrolled. Starliner Towers becomes a high rise hell of erased identities, plague, sex, and death.

A major caveat needs to be inserted (!) here. I don’t believe that Cronenberg is equating sex with evil or shame. If anything, shame is removed as surely as all other inhibitions vanish with infection. What Cronenberg has done a scary good job of is depicting the results of unchecked desire as equivalent to the both self-consuming egotism and erasure of the self as a being’s maturation and growth. The use to which sexual transgression is put here isn’t merely cautionary or simplistically moralistic; it’s a call to understanding how deeply meaningful the field of the body is as it is our experience of ourselves and others in the world. Sex is the point of origin for life, for gender (not the same as “sex”-as-identity), and the nexus for physical intimacy and the emotional connections that engenders. To see it transformed into something pathogenic, invasive, and/or fatal drives home and renders the film’s themes less abstract and far more visceral than a zombie or alien invasion might.

At the heart of “Shivers” is a couple who are the last two survivors, though it actually comes down to only the man being the last one. This is now a pretty typical trope, but nonetheless remains disturbing, as we see the horde of infected slowly move toward him and the camera switches to an aerial view of cars leaving the Starliner Tower to head to Toronto to begin infecting the world at large.

Inasmuch as I don’t think Cronenberg is sex-negative, he recognizes or sees in sexuality, death as well as creation, desiccation and erosion as well as intimacy and seems to tease out a kind of gynecological terror for female characters and a kind of fear of death by penetration for his male characters. Still, in “Shivers”, we can’t escape the seedier aspect of the proceedings. Hell, Dr. Hobbes is a type of “dirty old man” character one step away from a flasher in a raincoat. And it’s just this - along with some other elements - that elicits the occasional wry smile, if not chuckle.

Additionally, “Shivers” presents a kind of pan-sexualism that triumphs through a kind of Sadean (as opposed to Nietzschean) will to power. I don’t want to force too much of any one kind of reading, but with Cronenberg, as with the Marquis, there is a kind of forward momentum of freedom, power, and sex/desire that manifests as utter appetite. Also, as with De Sade, there is perverse humor throughout.

I wouldn’t call “Shivers” a laff-riot, but it would be wrong to look at it so thoroughly po-faced that we miss the humor in it. It is satirical and does assault the status quo of received morality, but it also questions, I think, the validity of an “anything goes” approach to getting what we want, while at the same time subverting it by showing what happens when we assume freedom as lack of restraint; it’s horrifying and alluring simultaneously.

Humor is often present in Cronenberg, not just as a textual element to dispel tension so much as a knowing wink and a nod at how hairy and inherently ridiculous/scary this all is. As in works by other filmmakers from Hitchcock to Lynch, humor shows up in dialog, visually, and inherently in the premise and execution of any given scene. No, we’re not laughing when an old man invades an apartment, beats and chokes a girl to death (and attempting to kill a parasite by gutting her with a scalpel); but we might start finding ourselves bemused with this scene intercut with with the signing of a lease and discussion about amenities and so on. Of course, my writing this is not going to convince anyone that this is funny, and to be sure, the humor is very, very dark.

Nevertheless, the humor is there and we can thank the filmmaker for that. Otherwise, we might be looking at something like a Canadian precursor to “A Serbian Film”.

There is a linear progression in these early films. Cronenberg stakes out his territory; science fiction, body horror, interrogations of power structures at societal and individual levels, sexuality as innately laden with danger, if not death, and so on. The progression from “Shivers” through “Scanners” is that we see the contexts shift and broaden. If the through-line is principally a Burroughsian sense of viral adaptation speeding humanity toward a different form (the New Flesh is just on the horizon), the arc begins with sexuality-as-virus in “Shivers” and “Rabid” (where it is weaponized by the protagonist) to birth as the vector by which rage and emotional dysfunction spread out in “The Brood” to utter psychic manipulation and the will to power-as-social disruptor in “Scanners”.

That might be a little too neat a package, but it’s how these films appear to me. Believe me, I think there’s even more going on in them, and they are frankly, incredibly, as entertaining as they are disturbing.

“Rabid” (1977)

With “Rabid” (1977), the intimacy of sex is weaponized as I’d mentioned earlier and the resulting trauma is constant throughout the film. Marilyn Chambers deliver a hauntingly naturalistic performance as a victim of a motorcycle crash who undergoes an emergency surgery to save her life that entails an experimental tissue regeneration procedure developed by the plastic surgeon who saves her. Her boyfriend Hart (Frank Moore), who was driving the bike, is released with minor injuries by comparison as Chambers’ Rose lies in a coma. When she comes out of it, well, let’s just say she’s got an appetite.

That Rose is patient zero for a disease transmitted by another phallic red stinger protuberance that enters the host when she penetrates the victim seems to carry on the themes of invasion and boundary transgression - the body is violated, the self is violated; but there is a shift in the vector. She is not aware that she’s the cause of a plague. She gets hungry both literally and metaphorically for contact and the result is either reluctant or outright horny men paying the price. There is a different dimension to desire/want or need here from “Shivers”; the stakes are higher emotionally.

There’s also a subtly political dimension to Rose’s viral spread. Her physicality is impressive and she has no issue with pursuit of her prey. I don’t want to ascribe a completely feminist motivation or reading to the film’s textuality here, but it’s credible. On one hand, Rose just wants to be loved; but on the other, there are men who are more than willing (in some cases) to take more than is offered and in other cases, there are those who might actually be well-meaning but are devoured by Rose’s unrelenting and uncontrollable ardor, if we can call it that.

“Rabid” isn’t as graphic or quite as unhinged as “Shivers” and there isn’t quite the symmetry in the narrative’s advance that we see in the earlier film. Where in “Shivers” we see a greater breakdown of boundaries across the board - boundaries of social behavior, medical ethics, the safety of one’s own dwelling, one’s own body, and finally, the dissolution of the self from others - here we follow a spread of devastating need outward.

Cronenberg flips the script here in another way, as well. In “Shivers”, it is primarily the males that are the more violent predators once afflicted by the parasites. In “Rabid”, Rose carries the burden. Rose also carries the burden that the director can’t escape putting on her or any of his female characters. The “male gaze” is as invasive as the parasites in “Shivers” and as objectifying as Rose’s transmitting of the plague. There are myriad ways in which the gaze is utilized here that aren’t merely reductive, though.

I think Cronenberg was/is well aware of the ambivalence of employing the perhaps unavoidable projections of male desire/fantasy onto his female protagonist/victim/heroine-anti-heroine. If “Shivers” is a collection of parallels and opposites (I’m thinking of how each gender acts once afflicted; the males are far more aggressive and violent; the women more seductive but while also capable of aggression, much less so) and “Rabid” seems to be an investigation of the ambivalent nature of seduction/coercion, desire for intimacy/felt need for fulfilled lust as projected onto Rose.

As tempting as it is to want to construct an overarching philosophy out of Cronenberg’s films, I find much of his work far more curious about the human condition. As transgressive as much of his early work is, it is so for a sound reason: investigation and inquiry is often seen as impertinent and outright threatening. I don’t know that it’s necessary or sometimes even useful to extrapolate some grand societal critique out of his work (though since the scope of the horrible events in his films transcends the individual, it seems unavoidable), but it his films demand very much that we take closer looks at what comprise human relationships and how we come to terms with ourselves and others as sexual beings.

We encounter the Other repeatedly and attempt to “only connect” but many times, what we find is not what we expected. Cronenberg’s an expert at inflating and exaggerating the unease we feel in an uncomfortable relationship; the allure of Marilyn Chambers as Rose is countered and contradicted by what she does to survive and the destruction of the men (and women, eventually) that she comes in contact with.

The differences, too, are in the type of disease that drives the plot. In “Shivers”, one could argue that the absorption into a sexual-maniacal collective of like-minded (possessed) zombies isn’t the worst thing in the world. In “Rabid”, Rose is just spreading a kind of rage fueled rabies that drives its victims to consume more flesh, go comatose and die.

The origins of each pestilence are similar: medical experimentation with half-assed motivation and no oversight, carried out with extreme hubris. One spreads out from a high rise, the other from a clinic; but in each movie, the spread is rapid and unnervingly relevant to us today. I suppose there’s a sense of humanitarianism on the part of the doctors/scientists who perform their experiments, but at the end of the day, the motivations are essentially, let’s see what happens if we do this, and I can’t help but feel that informs much of Cronenberg’s approach to his scripts here. The films are inquiries, interrogations, and investigations of our biological, gynecological, ethical, mental, and societal relationships and components as much as the doctors and scientists in the stories just want to find out what happens when you start poking around or developing solutions for problems that are probably better met with other approaches. In one sense, a more measured approach or more didactic film might present a more coherent or less confrontational/assaultive story; but god, would it be boring.

As it is, Rose anchors the plot and infuses genuine pathos into the story; by comparison, because the other characters are clueless about what she’s enduring, they come across as solitary naifs or helpless, inevitable victims absent of any agency. Even Hart, once he starts to piece together Rose’s plight is ineffectual. Rose’s best friend Mindy is sympathetic but has no conception of what her friend is capable of and all the while, the plague is spreading across Montreal. People are going crazy, murdering one another, dying, and a curfew is imposed.

Snipers are deployed to kill the infected and Rose meets her end when she’s picked off and dumped into one of the garbage trucks deployed for containing corpses. It is a grim end to a film that I find more terrifying than the zombification ending of “Shivers”; perhaps because it seems to mirror contemporary debate surrounding how we dealt with the coronavirus pandemic and how the virulently divisive nature of debate about masking and vaccinations is met with their opposites; similar discomfort and unease arises when we also consider the various laws in certain states that promote turning someone in if they have planned or did have an abortion; or for that matter, the threat of violence surrounding political discourse regarding LGBTQ rights and the protests against draconian laws passed to erase those rights and identities. The possibility of being picked off by a disgruntled citizen doesn’t always feel that remote or unlikely.

More to the point, and removing such contemporary considerations, the uncaring treatment of Rose as “just a dead body” is the final objectification of her being. That in itself is chilling. The what-ifs that abound beg consideration: what if her condition had been discovered sooner? What if the growth of her bloodlust had been arrested? Or put another way, what if we concerned ourselves more with understanding what constitutes our relation to the Other?

This might be way too obvious, but Rose is very much the isolated self amidst a world of others who well-meaning though some may be, cannot know her experience and she has no way to share that beside destroying the Other. This is one of the reasons why any societal critique comes second to ontological precedence in Cronenberg’s movies. By universalizing Rose’s experience, we end with a society of individuals who can no longer relate to one another except via hunger, rage, and destruction. Eventually, the uninfected will simply eliminate all the brutes.

It’s also in this terminus that Cronenberg introduces another theme; how transformation and the transformed are very often dealt with by the broader/more normative society. Leaving aside for a moment whether Rose’s transformation is benign, she remains human and by her dismissal as a human being particularly one that is now possessed of a different way of being, relegating her body to garbage status is an indictment of how “inconvenient” people are dealt with, but also, how we move to eradicate what we don’t understand. Admittedly, in light of contemporary events, it is extremely likely that Rose wouldn’t find particularly nice reception were she found to be the singular point of origin for such a catastrophic plague, but the criticism still stands: as a metaphor for approaching the novel, the new, the innovative, and so on, Rose’s transformation going unacknowledged and ignored by the authorities is an example of how new directions and approaches are perceived as disruptive, if not dangerous.

Even assuming that the script had Rose’s condition as beneficial, it’s worth considering that she would no doubt be exploited or weaponized. Call me cynical, but I’m inclined not to be favorably disposed to the idea that even salutary ideas are not eventually subject to capitalist-corporatist exploitation (and since we’re in the realm of science fiction, military distortion).

“Rabid” is not as overtly sexy as “Shivers”, but it might be more sensual. There’s are warmer, cinematic framings and the color scheme is more inviting. If both films are aware of architectural spaces, “Rabid” is built around or perhaps more accurately, as Rose’s space. I think this the first film where Cronenberg ventures into a single protagonist’s psychology and explores her situation more fully from her perspective; this creates a dichotomy, if not narrative conflict, when we zoom out and the scene cuts to someone else in the film. It rather reinforces what was said above about how ineffectual and/or incapable of grasping the enormity of what Rose is experiencing that adds to a greater schism between the individual and the communities in which she finds herself.

Cronenberg increasingly shows himself to be more purely an existentialist filmmaker than even, say, Bergman. To be sure, much of Bergman’s work does focus on the inability of individuals to simply connect with, much less understand one another. Bergman’s characters derive from a long tradition of interrogating the barriers that prevent deeper or more authentic relationships and for sure, much of his work derives from similar insights found in Sartre, Camus, et al. But Cronenberg goes one better; he’s attacking the Cartesian split between mind and body. If anything, Cronenberg is questioning the validity of that division between biology and psychology, between self and other, between body and mind. Oftentimes, the body in Cronenberg transforms so quickly and so extremely, and the perceptions with it, that the split is reduced to practically nil.

We are faced with an increasing number of protagonists who embrace the often horrible - in other people’s eyes - transformations as positive changes. Rose, to be sure, is not one of them, but she’s not far from being one. She doesn’t even realize she’s the point of origin for the plague until later in the movie.

It’s telling that what drives her post-operation is a need for human blood as her sole nutrition. That her victims are so afflicted in turn, but turn into rage-zombies of sorts (presaging Danny Boyle’s “28 Days Later” by some decades) who then die is a variation on the idea that society punishes the new, the different, the unusual; anger inflicts those who are resistant to change, to new ideas that they find threatening or abhorrent.

There is a case to be made that Cronenberg reads societal erasure and crusades to exterminate the Other as central themes in his protagonists’ narratives. We as spectators might reflexively side with the snipers in “Rabid” who pick off the infected, but this should bring us to confront something very ugly in the way we reduce people to meat sacks, bodies to mere inconveniences to be done away with.

Cronenberg early on said he was on the side of the parasites in “Shivers”; this should be a key to all his works. Whether it’s Max Renn, Seth Brundle, or Rose, each one has encountered a transformative truth, something that renders them horrible to the quotidian, to the “normal”. In at least two of those cases (Seth and Rose), they garner our sympathy, transforming from humans in search of affection to monsters in the eyes of others who are gaining increasing awareness that they have transcended, in a way, the limitations of others’ flesh, of - in some way - the Self, but who also realize they have no place among humanity. Of course, where Brundlefly chose suicide, Rose was murdered. Renn, too, was lost (but frankly, not the most sympathetic of characters).

In other words, we do feel their angst. Rose comes to the realization of the consequences of her actions (though these were, for much of the movie, unconscious) and we see how she is swamped by the wave of the tragedy unfolding around her. The apocalypse is personal.

It is also with “Rabid” that the twinning and alternating of protagonist-as-victim : protagonist-as-assailant is more pronounced. More so than in “Shivers”, there is a sequence of splinterings of identity/role for almost every character in the film. Sure, Rose goes after or attempts to go after only the lowest or meanest type of person (mostly male, but women are not exempt, like the patient in the plastic surgery clinic who keeps coming back for tweaks to her appearance). However, aside from the drunk in the barn, it’s difficult to completely justify her kills. The truck driver wasn’t predatory and even her final victim, in as much as the platform was framed as him picking her up, it was consensual and the guy was not a creep.

The most tragic, of course, is Mindy who Rose really didn’t want to attack but couldn’t resist the overpowering need within.

It’s worth considering here that, long before he filmed “Naked Lunch”, a case could be made that Cronenberg was filming a series of movies based on Burroughs’ “Algebra of Need”. In “Rabid”, the parallel to drug addiction is fairly overt and/but it demonstrates how “need”, not necessarily “necessity”(1) is a driver in our becoming, in how — often haphazardly — the personality is formed. With the next film, the concern with rage and sexuality is refocused and redistributed to also include the tragedy of a family falling/fallen apart.

“The Brood” (1979)

“The Brood” (1979) is Cronenberg’s first film with an A-list cast that begins to look into the ramifications of the weaponization of those with special powers. Just as a side note here: what would an X-Men movie directed by Cronenberg look like? We’ll leave that alone. Probably forever. Let’s get on with this, one of his most divisive films for a fairly specific reason/reading.

As mentioned earlier, I am not relying on biographical material from Cronenberg’s life, but in the case of “The Brood”, much has been made of the fact that he had gone through a sloppy and ugly divorce including an awful custody battle. Consequently, “The Brood” has been interpreted through that lens and while it’s difficult to say that life events don’t have an impact/influence on an artist’s works, the actual work is often more complex than that and interpretation shouldn’t be tied to those biographical elements to the exclusion of alternative/additional readings.

That said, Cronenberg has acknowledged the impact his divorce and the collapse of his family had on the work but/and another driving factor was the film as a response to tidiness/sugary nature of “Kramer vs. Kramer” and others like it that hardly capture the ugliness of divorce. It is also absent of humor - more so than even than “Rabid” (which did throw us some bones, so to speak, here and there.)

“The Brood” is tough going in a way that is far more disturbing than the genre conventions in the film. Frank Carveth (Art Hindle)’s ex-wife Nola (Samantha Eggar) is in isolated therapy undergoing a “treatment” that actualizes rage as a physical organ outside the body. Frank discovers marks on their daughter’s body when he is bathing her and this generates a confrontation between Nola’s therapist Dr. Raglan (Oliver Reed) and Frank that goes nowhere at first, but eventually comes to a head when Raglan is forced to recognize that not only is therapy harmful, it is catastrophic.

However, we could see a therapeutic value in the objectification of rage as a result of an awful and traumatic childhood (Nola’s mother was physically and psychological abusive and her father a passive enabler and useless in intervening for his daughter’s sake); what we get, though, are murderous toddlers that carry out Nola’s anger on a range of victims, including her mother while she is baby-sitting Candice, Nola’s daughter. This may sound funny, but in execution, it’s anything but. My first impression was of the murderous dwarf from Nicholas Roeg’s “Don’t Look Now” multiplied.

The murder-children bludgeon Nola’s mother to death in a quickly edited sequence where the violence is felt through the visual spattering of blood on wall and appliance more than shown directly on the dying woman. The impact is multiplied when Candice opens the door to kitchen and witnesses the carnage. It is one of the most jarring sequences in any Cronenberg film; the absence of any Grand Guignol graphic body assault is more disturbing for the sound design and editing and its conclusion in a granddaughter discovering her murdered grandmother.

By this time, Frank has confronted Raglan and enlisted the aid of one of Raglan’s former patients who describes Nola as “the queen bee.” Until the denouement, we can’t quite clearly conceptualize how Nola is birthing all these murder-children; when we do find out, it’s one of Cronenberg’s finest moments of body horror.

Before we get there, we spend most of our time with a male protagonist in contradistinction to the previous film. There is a tendency to see Cronenberg’s men as passive or ineffectual in the face of his women, often aggressive and efficient machines of destruction in these early films. That’s not quite how they read to me.

Admittedly, no one is particularly able to stem the tied of the onslaught in “Shivers” and Roger St. Luc (Paul Hampton) and Joe Silver’s Rollo Linsky failed to inoculate the afflicted and Hart in “Rabid” couldn’t help Rose, but then, neither could Mindy or anyone else. In “The Brood”, the men are successful at staunching Nola’s assault (to a degree), but this plays into the broader dynamics of Cronenberg’s themes.

It would be naive to claim that Cronenberg’s more problematic choices for his female characters are clear-cut. Rose alternates between being an object of desire, a woman possessed of great power, a victim of circumstance, an embodiment of anxiety and need, but not necessarily one of great agency. Nola has perhaps greater agency but is fueled by a different need and a more specific type of rage than that seen in either of the previous two films. Nola is also presented to us as more of a monster than Rose. She is also caught in a continuum of family abuse and while her rage is justified, there is attached to her a palpable sense of blame early on.

Dr. Raglan stands between Frank and Nola early on but Nola is hardly interested in seeing Frank, anyway. As a simulacrum for two spouses at war, it doesn’t take much to see how this is going. Right down to Candice’s being the major point of contention for both spouses, “The Brood” heightens the anger and anomie between spouses and the frailty of family’s in these circumstances through its horror movie framing of a domestic narrative.

Cronenberg is too complex a filmmaker to reduce the conflict in the film to a simple matter of siding with one character over and against the other. I don’t want to assume that Raglan is a stand-in or representative of other figures who interfere with divorce proceedings or who side against the husband and so on; indeed, Raglan comes around to see just how deadly Nola’s rage is and joins Frank in subduing it. That Nola dies might be some ex-husbands’ wish fulfillment, but there is nuance even in this that requires some review.

Honestly, of the four films at hand, I found “The Brood” the toughest going since the stage is domestic strife and the intimacy that involves; the rawness of emotions and spousal and parental entanglements unfolds in a barely contained simmer punctuated by bursts of violence - psychological as well as physical (we can’t escape Nola’s story) - until it culminates in the almost complete devastation of the film’s climax.

By design, our sympathies lie with Frank, but there is an uneasy sense that we’re only seeing one side of the story. I have my doubts that this is by design, but Nola’s voice is conspicuously absent in relation to the marriage’s dissolution. I realize that Cronenberg isn’t documenting the dissolution of his marriage and that there is a price to pay for interpreting any film through a wholly autobiographical lens. However, in much of his work, he’s often left inklings of complicity by the protagonists as elements of outcome, successful or tragic.

There’s also the theme of Nola birthing Rage Babies and sending them into the world to the ruin of those she feels wronged her. As a metaphor for how unchecked anger and sustained bitterness can lead to vitriolic ends of relationships and damage, it’s an unnerving, visceral, and even revolting ploy. It works, though.

By “The Brood”, the metaphorical approach to rage as a virus (“Rabid”) and a side-effect of tissue manipulation (“Shivers” - though, to be sure, the “rage” part of the epidemic takes second place to unchecked sexual aggression) to rage manifested in/as children as here, begs the question of what is it about the emotion that draws Cronenberg to examine it so much. Also, has it run its course?

The problem with “The Brood” is that it runs the risk of being a single-theme film where “Shivers” and “Rabid” had broader issues incorporated into the narratives. “Rage” is more of a signifier of frustrated urges to be overcome in “Shivers” and perhaps a righteous anger at in response to objectification in “Rabid”. In “The Brood”, we sense that it is less a response than a central, driving motivation on Nola’s part. This is what makes “The Brood” a harder to enjoy film than the other two; it’s focus is so restricted and so singular and the plot plays out so reactive that it doesn’t sustain interest in the characters to the degree that we remain vested in those in the previous films.

Raglan is an odd one; an obstacle that switches to pivot point. Early on, he’s defending his process, shielding/isolating Nola from Frank, and potentially threatening a father-daughter relationship. Eventually, he sees and accepts his part in the unfolding mayhem and pays the price in a sacrificial act of heroism. Oliver Reed makes it work. Raglan is by turns, smarmy, villainous, and human and Reed’s performance anchors it all in an example of grounded film acting; so much so, that the transition from obstacle to villain to redemption is relatively seamless.

Raglan-as-symbol, though? Is Cronenberg positing that relationships dissolve owing to outside, pernicious forces? We have seen by now that in the Cronenbergverse, instability and dissolution are results of stupidity, ignorance, madness, hubris, or some cocktail of all or some of them. In all the films, the men who released their misbegotten examples into the wild all come to regret their folly. With Raglan, there’s a solid redemptive arc that separates him from his predecessors. Why?

I’m supposing because Cronenberg the writer discovered he had a far more interesting character on the page than his earlier variations. Raglan is too interesting to be summarily dismissed. He died trying to rectify his mistake and while it’s not shot as an epiphany or celebration (his demise ain’t pretty) and helps draw the movie to its Pyrrhic conclusion.

While Raglan is saving Candice, Frank has begun his project of wooing Nola into at least letting down her guard as she gives birth to her latest Rage Baby. It’s a short lesson in slow reveals; as Frank and Candice talk back and forth, the camera remains in close-up and we cut back and forth. When it’s time for the latest spawn to come forth, Egger is lit from above in lighting that wouldn’t be out of place in Spielberg. She raises her arms to lift her gown that until then had been covering the extrasomatic fetus. Once her arms are raised, the camera does a slow pan down to the purplish mass in her lap. Art Hindle’s reaction is pretty spot on; Frank isn’t even sure what he’s seeing is real.

And then we see Samantha Eggar cradle the newborn infant in her arms - dangling umbilicus and all - and begin to lick the afterbirth from of the infant. The lighting is suffused and by now, Frank isn’t capable of much, much less hiding his revulsion, which Nola picks up on. She gets angry, the Rage Babies get angry. Raglan has gotten Candice about halfway through the dorm room and is holding her as the Brood comes to, in standing formation.

Frank tries to assuage Nola, but she’s having none of it. She’ll kill Candice before she gives her up and from here it’s her Eggar’s game; her rage is white hot and palpable. We cut back to Raglan shooing Candice through the Rage Barbie who let her pass as they begin their assault. Raglan has a snub nose and takes a few out, but the rest descend on him and Candice hides herself in a utility closet of particularly flimsy construction.

Nola pretty much tells Frank to kill her because that’s the only way she’s going to stop; she remains furious and I can’t recall when I’ve seen a character die more angry than Nola. However, while we are relieved that Frank chokes her out in time to save Candice, there isn’t much sense of catharsis. The entire film has been leading to this moment, but it’s a sickening sense of conclusion of purpose, not a release of pent-up anxiety.

Despite Nola’s history, I didn’t come away with any sense of resolution. It’s easy to read Nola’s demise as the only way to save Candice, but Cronenberg isn’t sparing us from the unease that comes with unresolved endings to relationships. Certainly, a death is final, but a divorce is not necessarily so. And here is where Cronenberg often shines.

None of his films that I can think of from this era and throughout the nineties leave us with a sense of a once-for-all conclusion. There’s a sense of on-goingness beyond the screen. Frank is not going to be happy about this; he’s going to live with this for some time to come. Even if, let’s posit, he’s not interrogated by the police or the whole ugly mess is simply hidden up, Frank has murdered his wife, the mother of his child. But of course, the trauma will continue through Candice, won’t it?

That conclusion is a pushing in to a close-up on Candice’s arm where we see a tell-tale sign that she remains infected and will presumably carry on her mother’s legacy.

That Raglan had developed a way to “weaponize” rage is expanded on and fleshed out more in “Scanners”, a tour de force that points the way forward to Cronenberg’s major works. In “Scanners”, Cronenberg is able to weave a far richer thematic tapestry and with a slightly longer running time than his previous features, and a larger ensemble, he produces a near masterwork.

“Scanners” (1981)

In a career that boasts several masterpieces, it’s arguable that “Scanners” represents the end of Cronenberg’s journeyman phase. There’s been a consistent command of the medium since “Shivers” and a steady and sure progression in that command up to and including “Scanners”. Much of what we encounter in the film is both recapitulation of the previous movies’ themes, but also points toward the direction Cronenberg will take in his work from “Videodrome” and “The Fly” and throughout other films like “Naked Lunch” and “ExistenZ”.

With “Scanners”, too, Cronenberg expands the thematic notion of a cabal or class that is outside and/or over/above the broader society. The previous films could be seen as serving as origin stories for potential sub-groups that would (could?) evolve outside the mainstream and possibly determine the fates of those in the mainstream. The warring factions between the Scanners could be taken as a Manichaean duality. It presages by 20 years the division between the mutants in the X-Men movies.(3) This particular theme recedes over the course of his work, but echoes can be found in “A History of Violence” and “Cosmopolis”, more explicit in the former as the mob that eventually comes back into Tom Stall‘s life and implicit in the latter as the Complex. How each protagonist responds/reacts varies but the shared theme is that the individuals challenge the power structure, altering it as in “Scanners” or destroying it as in “A History of Violence” (and possibly “Cosmopolis”? Once Packer is dead, does the organization continue without him?)

“Scanners” opens up more of Cronenberg’s unique ambiguity when it comes to human relations. Stephen Lack as the protagonist Cameron Vale is a precursor to James Woods in “Videodrome” and more of a cypher - at least, initially - than the his predecessors in the previous three films. He’s rootless and aimless and by all estimates, not a promising young man. He is, of course, a scanner and as such, has a limited lifespan. He doesn’t know what he is at the outset, but as he learns more, it becomes apparent to him that he bears a certain responsibility and joins forces with KIm Obrist (Jennifer O’Neill) and her group who have gained some degree of mastery over their powers and are fighting Dr. Paul Ruth’s Magneto-like opposition.

Cameron’s not strictly a “hero” and while he appears to grow into one, given the general themes of Cronenberg’s work when it comes to individuals and groups wielding power, it’s not clear cut what will happen outside the frame once Vale has destroyed Ruth (his brother, by the way). (4)

That said, Obrist’s group was something of an early example of a politicized group in Cronenberg’s work, perhaps of necessity. Like any marginalized group, there is the necessity for being seen, recognized, and respected. At the same time, there is push-back, often violent from the broader society and even from those factions like Ruth’s group. Nevertheless, there is a “liberation” being sought by Obrist and Vale. “What is ‘liberated’ in Cronenberg’s films is never simply benign, but is a play of forces at once personal and social, psychic and technological, in a society increasingly mechanized, rationalized, and yet deranged.” (Edward R. O’Neill “David Cronenberg” entry in Nowell-Smith, 1996, p. 736.) It is these tensions that have been there from the beginning but begin to become more palpable with “Scanners”.

The multivalence in “Scanners” is possibly more broad than deep or as emotionally resonant as in “The Brood”, but again, with Cronenberg, it’s not a simple matter of exploding heads and B-movie tropes for the sake of B-movie tropes.

To be sure, the film is as compositionally tight as the earlier movies and the architectural spaces seem to add more to the characters’ frames of mind. Indeed, architectural space in Cronenberg is as much an element of character definition as a close-up.

“I think it’s sort of semi-conscious. In the sense that a beautiful architectural space is a kind of an ideal. It’s a conceptual thing, an abstract thing, almost a philosophical thing. And then reality happens. Which is chaotic and messy. And it’s the conflict of the two, or the decay of one into the other. And it’s like what we were talking about before with Audis and entropy and all that. The human body is not architecturally very straightforward. It’s really, really messy. And yet from the outside it can seem quite—architecturally quite nice. But the interior—and this once again the exterior and the interior. The interior of the body is really chaotic and messy. And as we study—get down to the quantum level of examination of the human cell, we see how even more like that it is that we thought before. It’s not schematic. It’s not like those nice schematic drawings of the cell that you saw in high school. So it’s kind of interesting. It’s really, basically, intellect vs. the world. The desire for some kind of abstract purity and clarity.”

What do we do with all this?

In the recapitulations and summary analyses above, I’ve touched on themes and throughlines in Cronenberg’s oeuvre, many of which he continues to explore. Cronenberg’s films as texts ask us to engage with the visceral nature of existence, with what is often described as filthy, lurid, dirty, and so on. He places the body and its functions front and center as both an object for narrative exploration and a challenge to the viewer to examine the very nature of embodiment.

I don’t believe that Cronenberg sees the body (purely or exclusively) as an object of revulsion, but I do believe that he repeatedly asks the audience to investigate that sense of revulsion and look more closely at the preconceived/received notions of corporeal existence and identity as bound entities, if not the same thing.

Indeed, we see the physiological and the psychic collapse into a single experience. Alterations in the body come about simultaneously with changes in mental/emotional processes. This shifts a little with “Scanners”, but the sense of the manipulation of the world by intention still provides that thematic exploration.

The world we inhabit in these early films is the body. The body is very much the world and we can’t seem to escape the damage we do to one another or ourselves. There is absurdity throughout each of these films that point up the failure in our attempts to commodify or improve through technology intervention, the body. Often, our intentions to do so result - in these films - in utter disaster.

The trumped-up, often lugubrious hermeneutics that scientists and academics employ in these films seem like codes to underscore that humans know nothing about themselves and that we doom ourselves repeatedly through our efforts to manipulate or capitalize on our embodied worlds, our bodies themselves. This isn’t a matter of the trope of interfering with “Nature” or “God”; Cronenberg is not so facile. These early films lay the groundwork for, and in many instances are themselves, a politics and ethics of embodiment.

There are vital questions that we as social questions avoid dealing with because we exist far too often in conceptual constructs. It isn’t until we encounter restrictions on our movements or our economic well-being or for that matter, our futures, that we come back to ground zero; the body.

We encounter existential threats all around us in a damaged environment, in wars, and in some countries like the United States, attacks on reproduction and women’s rights to full autonomy. We could drill down and see the intersection of capitalism with armed restraint and oppression in all of these works.

Cronenberg also doesn’t shy away from the abuse we inflict on one another prior to the transformations that characterize his body horror imagery, the primary example being Nola in “The Brood”, but also, Cameron Vale in “Scanners”. The horrors begin earlier on and it’s sometimes obvious that getting lost in external solutions is not the optimal approach. However, having said that, psychiatry doesn’t seem to avoid a thrashing from Cronenberg, either.

That these early films are narratives of the biological with the technological (genetic modification, heightening of mental powers through mechanical assistance), it is the biological that continues under its own steam once free of reliance upon the initial modification. “Life finds a way”, to pull from a different film and filmmaker. Unlike “Jurassic Park”, though, “life” in the films of this part of Cronenberg’s filmography is far more insidious and debilitating. By the time we finish with “Scanners”, we are about to be exposed to “the new flesh”, but that flesh is found all throughout these earlier works.

To be sure, Cronenberg’s vision of the world and the body-as-world in these films is fraught with danger, despair, and absurdity. This would be bleak but for the demands that the director makes on the audience to consider the narratives as philosophical texts. I doubt he’d put it that way and might even disagree with that, but it is difficult to believe that an artist who mounts so consistently, works of such philosophically charged material, doesn’t want to promote some degree of engagement beyond the mere entertainment aspect of these films.

It’s not too much of a stretch to say that the real villains in these films are not simply technology, but capitalism and patriarchy. Capitalism renders body as commodity for optimization and market exploitation, either as an object to be “improved on” or as a weapon to be utilized. The critique of patriarchal values is inherent throughout Cronenberg’s work and despite “The Brood” as being critiqued as misogynist, I find that it’s not wholly that. If anything, “The Brood” recognizes the director’s own complicity in perpetuating a patriarchal narrative of masculine dominance as expressed through male “scientific” arrogance (Raglan) and/or extended via passive assumption (and exacerbated by ineffectuality in understanding, in Frank).

The first, if not primary, element that asks us to and points the way to engagement with the early strata of Cronenberg’s works, is simply just asking what it means to be embodied. The first element is so central to his work and has been referenced enough throughout this piece, that I don’t think I need to write another consideration of it right now (though I will come back to it later). The second element is - and I want to look at this a little more later - the ethical; how are we to relate as we react to and live in a world where our bodies are manipulate, commodified, and often with less than desirable results. The third element is the sexual/relational. By this, I don’t meant mere “sexual relations”, but how Cronenberg challenges the audience to interpret sexual dynamics. He’s not quite there yet with the sexual politics of, say, “Dead Ringers”, but there is a lot to explore in the sexualities in these early films.

On that last part, heteronormativity doesn’t quite come under full-on critique, but there is a queering of relationships between men in “Stereo” and “Crimes of the Future” that feels like the germ of an idea he would revisit in his later work. But there are hints of critique implied throughout the features of this period, more along the lines of the toxic heteromasculine and less an exploration of non-heteronormative male relations. Nevertheless, the power dynamics between the sexes is baldly expressed through the treatment of the heroines: Chambers in “Rabid” and although she is not presented as heroic, Nola in “The Brood”; but also, Kim Obrist in “Scanners”.

In the first two cases, they are acted upon first, but then begin to exercise their wills and agency, if with disastrous consequence. Obrist, conversely, falls more into the genuine heroine role and is more of a guiding figure (I don’t know if I’d go too Oedipal on this, though it may be subtextual by default) to Cameron. Conversely, the joke is on the men who support the technological enhancements to embodied existence. Useless or dangerous organs are developed and evolve outside the body; emotional distressed is exaggerated and capitalized upon; the humanistic tragedies quickly fall back on the authors and subsume a wider community or collective, if you will.

I say “joke” intentionally. Again, not to say that Cronenberg’s films are laugh out loud funny, but they do contain and convey a sense of the absurd that isn’t too remote from classical absurdists like Artaud or Jarry.

In terms of ethical considerations, I am not thinking in terms of an overarching “morality” or systematic ethical stance or system; I find that Cronenberg’s films are rife with questions about how we treat ourselves and each other and where we bump up against delimiters of the flesh, the market, society, and the world itself (which to be sure, is that in which we live and have our body and by extension, by engagement with it, is “the world”).

The ethics across Cronenberg’s work and beginning with these, are critical considerations of the uses and abuses of power, particularly, exploitive power of governments/corporations/capitalist societies; but also, of how we can better navigate our own experiences as beings-in-the-world. There is little room or textual explication of altruism or benevolence in the Cronenbergian milieu, at this stage. We see a more comprehensive unveiling in his later works, but even then, motivations collide with violence (literal, as in “Eastern Promises” and “A History of Violence” or psychological, “A Dangerous Method”).

All of these are located in embodied existence and its (sometimes literal) dissection in Cronenberg’s film work. These first four features (and the two smaller works discussed) lay an extensive foundation for what would come later but it is fascinating how many different approaches Cronenberg has taken to his themes. It is also frustrating how often critics and reviewers continue to view his work through the lens of “body horror” almost exclusively. To be sure, he made his name and reputation on the back of works like those examined here (and of course, well through the 80s and into the 90s), but he has taken non-horror genre avenues that haven’t strayed at all far from his critiques of how people relate, of our relations as bodies in the world, and the corporatist-capitalist exploitation that informs contemporary life.

Naturally, his forthcoming feature “Crimes of the Future” is highly anticipated and it should be obvious that I for one, am looking forward to it. It will be interesting to see how much he uses from the earlier work; it’s already been said that the development of organs outside the body is part of an engineered “evolution” and if memory serves from the one review I looked at, how to commodify that tech. Judging from the previews, things go tits up in remarkable Cronenberg fashion.

Yes, it’s David Cronenberg, two appendices.

Notes:

- Cronenberg in MacInnis (1).

- Of course, this is not to say that the themes Cronenberg is dealing with are not universal or timeless. However, that their applicability is so pointed is worth noting, if only because in many ways, so little sometimes feel as if it has changed.

- I realize Professor Xavier from the X-Men predates Cronenberg’s filmography but he would fit in with the Scanners; it could be argued that there is a resonance between Cronenberg’s early use of body horror, mind control/telekinesis, and other elements and many narrative aspects of the Marvel comics of the period.

- That parenthetical note is another in a long line of “wait, what?” family reveals from Darth Vader to Ernst Stavro Blofeld as played by Christoph Waltz in “Spectre”. However, it has more narrative weight as we realize that Paul had manipulated Cameron for much of his brother’s life. (The parallels with the Bond movies might be worth fleshing out; did Purvis and Wade see “Scanners” and think, “huh, we could do that to Bond”?

Bibliography

Adams, Sam. “Two early Cronenberg efforts fuse genre and personal themes“. The Dissolve. https://thedissolve.com/features/upstream/184-two-early-cronenberg-efforts-fuse-genre-and-person/.

Baker, Shelley F. Body-horror movies: Their emergence and evolution. Masters, Sehffield Hallam University. United Kingdom. 2000.Cr

Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: the Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press. Toronto. 2006.

Beaty, Bart. David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence. University of Toronto Press. Toronto. 2008.

Berlatsky, Noah. Fecund Horror: Slashers, Rape/Revenge, Women in Prison, Zombies and Other Exploitation Dreck. (Ebook) 2016.

Bottling, Josephine. Why I Love…The Brood. The British Film Institute. https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/features/why-i-love-brood. 14 April 2020.

Brehmer, Nat. Why David Cronenberg Gets Heat for His Portrayal of Female Characters.Wicked Horror. https://wickedhorror.com/features/editorials/why-david-cronenberg-gets-heat-for-his-portrayal-of-female-characters/. September 18, 2015

Burgess, Steve. “David Cronenberg”. Salon. https://www.salon.com/1999/11/30/cronenberg_2/. November 30, 1999.

David Cronenberg: Digital Exhibition. http://cronenbergmuseum.tiff.net/accueil-home-eng.html.

Dudenhoeffer, Larrie. Embodiment and Horror Cinema. Palgrave MacMillan. New York. 2014.

Eddleman, Sara. The Postmodern Turn in Cronenberg’s Cinema: Possibility in Bodies. SHIFT - Queen’s Journal of Visual and Material Culture. Issue 2. 2009.

Goldberg, Daniel N. David Cronenberg: The Voyeur of Utter Destruction. The Morningside Review. https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/TMR/article/view/5532. May 1, 2008.

Hurley, Kelly. Reading Like an Alien: Posthuman Identity in Ridley Scott’s Alien and David Cronenberg’s Rabid. Posthuman Bodies. Halberstam, Judith and Livingston, Ira, editors. Indiana University Press. Bloomington and Indianapolis. 1995.

MacInnis, Allan (1). David Cronenberg Addresses the Critics. The Georgia Straight. https://www.straight.com/movies/615506/david-cronenberg-addresses-critics. March 26, 2014.

MacInnis, Allan (2). David Cronenberg Retrospective Goes Deep. The Georgia Straight. https://www.straight.com/movies/73759/david-cronenberg-retrospective-goes-deep. March 26, 2014.

MacInnis, Allan (3). David Cronenberg on the “Cronenbergian”. The Georgia Straight. https://www.straight.com/movies/73761/david-cronenberg-cronenbergian. March 26, 2014.

Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey, editor. The Oxford History of World Cinema. Oxford University Press. New York. 1996.

Shaviro, Steven. “Bodies of Fear: the Films of David Cronenberg”. The Cinematic Body. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis. 2006.

Williams, Linda. Screening Sex. Duke University Press. Durham and London. 2008.

Wilson, Scott. The Politics of Insects: David Cronenberg’s Cinema of Confrontation. Continuum International Publishing Group. London. 2011.

Comments

Post a Comment