“The Greatest Beer Run Ever”: just order in

No one sets out to make a bad movie. It is difficult to judge a work too harshly when the various people who work on any given project are taken into consideration. That said, some works fail. They fail to entertain. They fail to engage. They fail at just plain telling a tale with the bare minimum of verve, style, or panache. I rarely say that a movie sucks. I have said in the past but to be clear, I am not going to say it now.

“The Greatest Beer Run Ever” isn’t engaging enough to suck. It’s too milquetoast to generate a heated response. It’s too enervated and inert to elicit much of a reaction except, “Well, that’s too bad.”

I understand Peter Farrelly continuing to pursue films with stories that have something to say. It’s admirable when anyone decides to switch gears and work outside the familiar. That “Green Book” was recognized by the Academy is a lovely thing for Mr. Farrelly, however much it says about the Academy and its electoral processes.

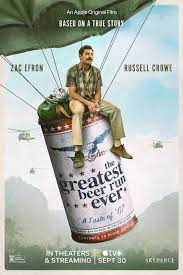

The movie at hand is unlikely to receive such recognition. Based on a true story of a young man who decided to deliver beers to his friends in Vietnam in order to cheer them up and let them know that they haven’t been forgotten, the movie has a compelling, screwball premise that could have been mined for substantial riches and reflection. The movie at hand is not that movie.

There is not an image, a scene, a line of dialog that evinces any but the merest thought was given to it. Zac Efron, the hero at the center of the story, John “Chickie” Donahue, is an aimless kid (I suppose he is pushing thirty, seven years younger than Efron) who, when he’s in port from his stints in the Merchant Marines, sleeps till three, hangs out with his neighborhood chums and runs up his tab at the local bar run by The Colonel (Bill Murray playing a one-note character..as a favor to Farrelly, maybe? It’s mostly an extended cameo).

His friends, none of whom seem particularly unique or even fun to be around are all gung-ho supporters of the war. Chickie’s sister is not and for a minute, you sense that that there might be a meaningful conflict here or some depth to portraying the oppositional tensions the war cast on families across the country. Instead, we get Chickie and his friends talking about what they could do to help the troops and after a bit, Chickie grandly states that he’ll go Vietnam and bring beer to their chums in-country.

It’s a dipshit idea coming from a dipshit character, but we are intended to read his declared statement of intent as mere empty words. To his credit, Chickie stands by them, and with a duffel bag full of Pabst, bids his sister farewell, gets in a cab and heads for a ship sailing to ‘Nam bringing munitions for the military.

Once in Saigon, Chickie begins to network. He meets journalists, including Russell Crowe as Coates, a photographer for Look magazine. It seems almost unfair to put Efron in the same scene with Crowe, partly because of the difference in caliber of actors, but also because both characters are so underwritten on the one hand (Chickie) and overbaked on the other (Coates is the wise, wizened, seen it all photog dispensing nuggets of wisdom at the drop of a hat). Maybe it really isn’t either actor’s fault about the disparity, but the dialog throughout the film is so labored and so free of anything resembling the way humans actually speak to each other, I put my suspension of engagement on hold all the way through.

In a series of oddball machinations that I genuinely believe are factual, Chickie makes it up to the north after finding one of his buddies in Saigon and thereafter, the film begins to advance at a slightly faster snail’s pace. Chickie has been mistaken as being a CIA operative because he is so very much a tourist, and dumbass, at that. Sure, he has a good heart, but his degree of self-awareness and ability to read a room is functionally nil; however, the universe and U.S. Army brass reward him.

Once he’s in the north, he almost gets the second of his friends killed by requesting he come in from ambush duty. We see him running through a hail of bullets and is rightfully pissed when Chickie reveals himself. Naturally, our hero doesn’t understand why and his friend’s sergeant tasks him with keeping Chickie safe. To his credit, he makes Chickie accompany him to his post; now with both men skirting getting shot up (as someone else has pointed out, the Viet Cong in this area must have had the worst snipers).

I think Chickie’s buddy’s name is Reynolds [EDIT: Tom Collins…I couldn’t not look it up]. I’ll let that stand and I don’t care enough to look it up. Doesn’t really matter; he berates Chickie and tells him to leave the next day, they’ll put him on a copter and get him out.

Aside from the general dumbassery of just being there, the next morning, as they’re leaving the post to return to base to get Chickie out, our man just had to say, “that wasn’t so bad.” Did the real Donahue say this? Probably? I guess? Does it define the character? Sure. Why not.

Chickie does get on a copter ride with a real CIA operative, a translator, and their informant and for minute, it seems that the movie will kick into a higher gear. The interrogation is just real enough and Efron comes to life when the CIA looks like he’s going to kill the guy. The informant gives up whatever it was they wanted and in one of those scenes that works best because the action is executed so matter-of-factly, the CIA agent lets the informant fall to the forest canopy below.

Captured in a wide shot, the sight of the single body falling head first is chilling and but for one salient detail, this scene would anchor the movie in something approximating the cruelty of war. But that one detail is all it takes to completely efface the drama and substance of this one scene.

Instead of simply, say, leaving the scene to play out in silence, the decision was made to employ a contemporaneous pop song (we’re in 1967 or 1968 by now). If I had to fuck up a scene with music, I would have chosen something with some relevance. I realize that Farrelly might not have wanted to use one of the usual Vietnam-era chestnuts, but “Cherish” by the Association is not the choice I would have made. This goes into my extensive collection of moments of “What the fuckery” that I keep in mind when I can’t believe what I’m seeing or hearing in a film.

Fine, fine. Whatever, as the kids say. As they draw near to landing and prior to exiting the plane, the Ops guy quizzes Chickie on who he is, what he’s doing in Nam, etc. At these moments, Efron actually comes to the party; he musters a bullshit brio and tells the Company guy that he works for the same guy, and some other improv as he heads to the base’s office to cajole passage to get back to Saigon.

The officer at the desk puts him off but says he could get back on the chopper he came in on; however, Chickie knows that’s a bad idea and demurs forcefully. The officer says he’ll see what he can do, comes back out and says he’ll take Chickie himself to the next base. Abandon his post to do that? Even Chickie isn’t that dumb.

Chickie escapes out the bathroom window and into the jungle and sees the CIA agent and translator with weapons drawn scoping out the bush for sight of our man who’s hiding in the shrubbery with a very large centipede for a scarf.

Cut to another shot that should have landed with more emphasis. Chickie is hiking along a road to his next destination. Dusk is falling and out of the fields that line the road comes a ball with a little Vietnamese girl following it. The ball rolls to Chickie’s feet and the little girl freezes stock still, with utter fear in her eyes. She doesn’t cry out, doesn’t sniffle, even, which makes her performance more gutting. Chickie tries to soothe her and tosses the ball back where it falls at her feet when the girl’s mother comes out of the field, sees Chickie, screams (which causes her daughter to, as well) and they vanish back into the tall grasses (bamboo? I didn’t get a clear shot of the vegetation they came out of.)

Later, Chickie encounters an elephant stampede in the darkness of nightfall and there is a sense that the film may be on a new path; something darker and more gripping. And the sense passes when Chickie finds his second pal on a patrol. Chickie tells him his story up to fleeing the base because he saw something he shouldn’t have and the film deflates. Chickie convinces his buddy to turn back and drop him at his destination and it looks like Chickie will get back to Saigon, and make it back to his ship and get back to the U.S.

However, there had to be a however, because this drudgery isn’t over. However, his ship has departed and he has to secure another means to get to Manila to meet it. And we encounter a wrinkle with the beginning of the first invasion of Saigon (January 1968 is when I’m assuming the action of our story is taking place.) Chickie had returned to the hotel bar where he’d met Coates and the other journalists, his sense of rightness about the war shifting, and then it’s explosion city. Once again, there’s the sense that a sense of dynamism might shift the static structure of the movie.

It doesn’t. We see dead bodies, a U.S. tank that blows a hole in a wall at the embassy to make it look like the VC and the North Vietnamese Army had done it, and Coates and Chickie hunker down in an abandoned house for the night. The next morning, they straggle through the streets and they see in the distance a huge smoke cloud over the base where Chickie’s last friend is supposed to be.

Chickie, for the record, has not relinquished his duffel bag of brews. How many does this thing have? Is this supposed to be symbolic? Is he a Brooklyn Jesus and the beers are his loaves and fishes?

He tells Coates he’s got to go there. He needs to know if his buddy is okay and they boost a convertible and get to base under the imprimatur of Coates’s press credentials. Yes, you’ll be happy to know that Chickie finds his pal, his pal is amazed at Chickie’s stupid but good heart and finds transport for Chickie to Manila. Coates in the meantime is not going to leave; he’s a war correspondent, this is his place. Again, all of this could have and should have carried some weight, but it’s all beyond or less than formulaic and by this point, I had long ceased caring.

Chickie gets back to NYC, pops in at the bar, tells everyone that the war is not a black or white issue, that it’s much more complicated than the government would have us believe and thus, we know that Chickie has evolved.

Chickie makes his way to the protest site, lights a candle, bumps into sister and says he’ll have to do less drinking and more thinking.

In a mid-credits (I think; maybe pre-credits) segment, we learn that Chickie and his pals are still around and Chickie got his GED and attended Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and became a trade unionist.

There is a genuinely gripping, amusing story in here, but the execution is so clunky, far too much to overcome by sporadic and variable performances.

I also appreciate that Farrelly is attempting to draw parallels between the polarization surrounding the war in the sixties and our current atmosphere of division. Indeed, there is some pointed dialog in the script to that effect that lands with so much import you couldn’t miss it. Well-intentioned though that may be, it only supports how facile and reductive much of this film is. It’s rubric that “the Vietnam War was complicated” and that Chickie’s growth may mirror the growing pains that much of the U.S. population went through is “nice.”

Unfortunately, Farrelly doesn’t have the hooks to flesh out something deeper nor any sense of a burning intention to fuel this tale. Unlike Adam McKay, Farrelly’s transition to a filmmaker with Big Issues on his mind isn’t there yet. Of course, you can certainly retort: “Well, Farrelly has an Oscar.” Fair enough; but in my experience of watching movies and especially many of the ones that the Academy has honored, and I remain unconvinced that an Oscar is a symbol of rewarding excellence or merit. Besides, McKay has one, too.

ALSO:

A couple of other observations. There are three Vietnamese characters that Chickie has some interaction with besides the mother and daughter. The bartender at the hotel bar, the translator (sort of an interaction), and Hieu, a traffic cop who befriends Chickie early on and whose body Chickie finds during the night of the invasion. The movie is getting dragged for its lack of presence of Vietnamese people in the narrative and while I somewhat agree more than disagree, I would argue that it seems to fit as a piece with Chickie’s myopia. In that regard, it’s very much in line with the U.S. involvement in Vietnam (and other places, to be sure.)

I love me some Russell Crowe. He’s never less than entertaining and frequently, a wonderful addition to any film he’s in as he is here. But why did they equip this photojournalist with a couple of instamatics (although I recall one scene where he used a telephoto lens) and why did the cinematographer and/or Farrelly, think that shots like these are dynamic or visually arresting?

Comments

Post a Comment