Vampires: still in season! Dreyer’s “Vampyr” and Portabella’s “Vampir”

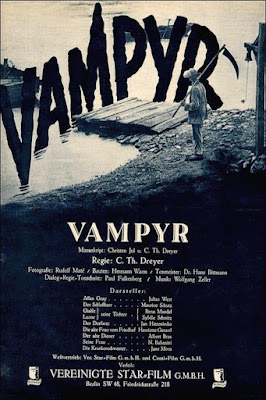

As the day draws closer, I really am increasingly inspired to watch as much “horror” as I can. Following my inclinations, I am bouncing across eras and the past couple of days, I decided to head back to 1932. Carl Theodore Dreyer’s “Vampyr” was shot over a longish period the previous year with Dreyer’s aim to make a film unlike any other. He succeeded admirably. Unfortunately, contemporary audiences and critics were not just unkind, they were antipathetic toward the enterprise so much that it was considered a minor work and best forgotten.

Fortunately, it is now recognized as a work that transcends the genre and is now very much remembered. I’ve seen it three or four times and each time, it grows deeper for me, particularly as an example of oneiric cinema.

It is often lumped in as a piece of expressionism, and a case could be made for it; but not the German expressionism of, say, Wedekind or Pabst, much less the proto-Expressionsim of Murnau. But Dreyer shares a sense of the dreamlike with Murnau and both had a distinct affinity for nature and man’s place in it as well as nature as part of humanity’s psyche. However, Dreyer remains unique from his contemporaries. There is a measured slowness to the proceedings here. Like his earlier masterpiece, “The Passion of Joan of Arc”, the camera is used to open up vistas and faces, and it lingers to open up time, as well.

In the earlier work, we are exposed to and centered in the tensions between mysticism and dogma, patriarchy and a single-minded woman, the love of God as a personal experience and the jeering of the priesthood and the camera’s gaze is steady and calls us to choose. We feel Joan’s pain viscerally through Falconetti’s face and it is a journey into the ethereal and toward something like divinity.

In “Vampyr”, the camera is far more kinetic. The images are hazy, almost imitative of a Redon pastel. Yes, if the Germans were Expressionists, our Dane is a Symbolist. Faces in close-up blur at the edges. The story is that cinematographer Rudolph Mate had taken some shots that came out hazy and Dreyer liked the effect so much that they shot the entire film through a sheet of gauze. It works; we enter a dreamworld that Cocteau would be envious of ( I don’t know that he was or if there was any interaction between the two; by this time, Cocteau had filmed “Le sang d’un poete”/“The Blood of a Poet” and while there is a shared sense of the logic of dreams in both, Dreyer is going for something different, something less universal - I think - than Cocteau).

Yes, the camera is in near constant motion. One dolly shot follows a character until the character disappears into another room but takes up when another enters in the foreground. There are tracking shots that would make Scorsese jealous and subtle uses of in-camera and practical lighting effects that reinforce the strangeness of the world we have entered.

Based on two stories in the collection “In a Glass Darkly” by Sheridan Le Fanu, Dreyer uses elements of them to compose the merest of plot; the overall tale he leaves vague enough to evoke a sense of the unsettling. We meet Allan Gray, a student of the occult coming to an inn near Courtempierre, France and strangeness begins almost immediately. The girl who lets him in we never see again (a later character will say that there is no child at the inn) and as he is attempting to sleep, the door to his room opens and an man enters who says “she must die!” He leaves a book with the instruction that it be opened after his death.

The man leaves and later, Allan takes the book and walks outside where he sees shadows dancing, another shadow digging in reverse (and earlier we had seen a gaunt bearded man with a scythe boarding a small boat, presaging Bergman’s Death coming in twenty-five years.)

The shadows guide Grant to a castle where he sees an old woman we will later come to know as Marguerite Chopin, the titular vampire and the village doctor (her Renwick to her Dracula, if you will). I wish I could describe the mill-building better; we don’t get a clear exterior shot, but the interior is angular and cubist almost. There is a one-leg soldier whose shadow joins him after its own sojourn, and credit to Allan for not disturbing any of the weirdings.

Eventually, he finds his way to a chateau where the lord of the manner - the man who deposited the book with him earlier - is murdered; shot in the back. The servants let Allan Gray in but he is too late to save the man. He learns that the fellow had two daughters Gisèle and Léone. Léone is gravely ill; but before long we see her walking the grounds in the moonlight. Allan and Gisèle go after her and she is returned with the aid of the servants. There are strange marks on her neck and it is not long before Allan discovers these are the bites of a vampire. The parcel he has carried with him is a book about vampires and he puts two and two together.

The village doctor shows up (Gisèle asks the manservant, “why does the doctor only come at night?”) and Allan follows him to Léone’s room. He is told by the doctor that she needs blood and Allan volunteers. Gray passes out from the transfusion and wakes to find the doctor trying to poison Léone. They fight, the doctor flees, and Allan finds Gisèle gone. So far, so good.

Nothing is terribly weird in any of these more immediate sequences, but a sense of unease grows in the editing. We cut back between the doctor and Allan to the manservant who is now reading the book. While Allan learned what vampires are and what they do, the servant discovers how to kill them.

In short order, Allan pursues the doctor across the grounds and tiring sits on a bench where he has an out of body experience. It’s neither a dream nor a vision; we see his “ethereal body” detach from his physical one and begin a journey to the mill where he sees his body in a pine box coffin being nailed shut. The P.O.V. shifts to Allan’s inside the box as the doctor and Marguerite’s faces look down on him. In a super use of just letting the camera see what it sees, we are there in the coffin as they carry Allan Gray away, passing by where his ethereal body had left his physical body. He revives on the bench and the coffin and its bearers vanish.

Making his way back to the mill, we find Gisèle tied to a bed in one room and the ghost of the lord of the manor striking terror into the doctor and the soldier who flees. The doctor tries to but finds himself caged in the mill’s grainery which is soon filled as the gears and wheels turn and bury him where suffocates.

Allan frees Gisèle and aids the servant in disinterring Marguerite Chopin who drives a metal stake into her, releasing Léone from her torture. As she revives, Gisèle and Gray cross the river and move from a foggy, shrouded scene into a bright by-now-dawn/daylight clearing.

None of this conveys the beauty of what’s on film or the strangeness of each scene or the performers inhabiting those scenes. Once you do see it, though, “Vampyr” does show itself to be unlike its predecessors and contemporaries. The measured pace, the studied moments, the deliberately slowed frame rate generate a contrast to the more showy aspects of, say, “Nosferatu” or even Cocteau’s work (beautiful though it is).

The sound design only adds to the picture’s strangeness, dialog and sounds added in post. They aren’t necessarily out of synch (of the actors, I think only Nicolas de Guzburg who played Allan Gray covered his own voice). The musical score by Wolfgang Zeller is never so obstructive or leading as many in the horror/suspense genre. It seems to maintain a kind of impressionist almost proto-ambient pastoral feel. Even this only adds to the lushness of what unspools.

As for the performances, Dreyer received partial financing from his leading man who insisted on being in the film as a trade. De Gunzberg (under the pseudonym Julian West) was a magazine editor and socialite. His biography on Wikipedia is a hoot and worth a read. Under normal circumstances, his performance would be described as wooden, but these are not normal circumstances. His dead-eye, almost somnambulant gaze reminds me of the magician David Blaine and in the context of the film, is a perfect fit.

Most of the cast were non-professionals but this only adds to the disconcerting poetry of the film. Indeed, there’s a freshness to the way people carry themselves in the film. There are no exaggerations of gesture or overwrought facial contortions trying to sell an emotion or moment and this adds another layer of uncanniness.

If anything, almost all of the elements that make this film so fascinating would show up in later works and find a kind of apotheosis in more contemporary filmmakers, from Tarkovsky down to Lynch. As an example of the genre, the disconcerting nature of the film remains but is rendered lyrical, though this doesn’t blunt the uneasiness of what we see before us.

The film’s end may read as a kind of hopefulness, but/and it could just be a waking from a nightmare.

The gallery of images following give some idea of the feel of Dreyer’s work. The use of rectangular planes allows for sense of movement between a psychic as well as geometric space.

If the close-ups in “The Passion of Joan of Arc” were landscapes of psychology, revealing character, the close -ups here reflect a dreamlike, somewhat miasmatic state on the border of waking and sleep. Or perhaps, death.

Last, a sequence of images that demonstrate Dreyer’s debt to artists like Fusili and Redon, certainly Symbolism, but even a nod to the Pre-Raphaelites.

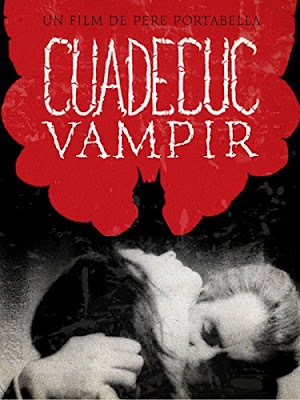

Pere Portabella’s “Cuadecuc-Vampir” (1971)

Portabella’s “Cuadecuc - Vampir”, is an hour of near postmodern deconstruction of the Dracula story using behind the footage from “Count Dracula” (directed by Jean Rollin) that includes scenes with cast, crew, and set-ups. It is for the most part, a silent film (with Christopher Lee’s explanation of the end of Stoker’s novel, the only dialog), although there is some music and sound effects used now and again.

It is itself a ghostly product, a ghost of a film. Portabella began as a producer and then moved to more avant-garde and abstract filmmaking before delving deeper into more political narratives (and becoming a politician himself). It is, of course, a meta commentary on the nature of filmmaking, but it also remains a vampire story in terms of bringing to life the cast-off footage, the “worm’s tail” of found footage, a kind of vampirism in and of itself.

And whew: it is a striking piece of work! Shot on high contrast film, some of the images are hard to read but like Kodalithic Rorschach tests, come into view to be replaced by more legible sequences. One minute might be an actor caught unawares on film in the distance, another is a crew setting up lights, a third might be much of an entire scene from Rollins’ opus shot from a very different point of view.

There is a potentially political dimension to Portabella’s enterprise, as well. Katie Duggan at Filmdaze, points out the clandestine filmmaking of “Vampir” mirrors the surreptitious filming many had to resort to under Franco and the deconstruction of Dracula as a metaphor for deconstructing (and de-fanging?) the dictator. (It’s a terrific essay; give it a read.)

Comments

Post a Comment