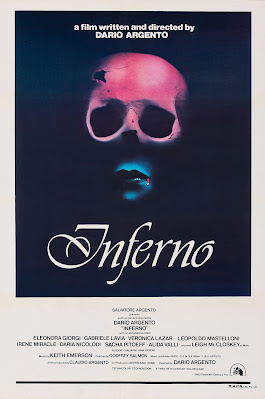

Identifiably Argento - “Inferno” (1980)

Italian giallo is the most operatic of horror cinema sub-genres. At its best, the genre is comprised of works that are unsettling at a deep level, characterized by hyperstylization, and often, characters who read less as people than somnambulists caught in waking nightmares, aware of unavoidable fates. The names Mario Bava and Dario Argento loom largest over the landscape with the latter still active at 82.

Of the two, I prefer Bava’s work overall. He was more disciplined and assured in his storytelling. While many of the elements mentioned above are present in his work, he did seem to care more about his characters than most, and I should hasten to note that Bava also worked in other genres, from sword and sandal epics to spy fiction a la James Bond (“Danger Diabolik” is so many kinds of awesome).

Argento, by contrast, is almost pure opera. “Suspiria” and “Bird with the Crystal Plumage” are usually regarded as his masterpieces, but I would add a couple of others to the mix. “Deep Red” and even “Tenebrae” (which many would disagree with, but I’ll stand by) are the other two.

I think I feel Argento to be more of a poet than Bava. It isn’t worthwhile to go looking for tightly scripted plots are well-drawn characters (though in more than a few cases, he has had actors like Jessica Harper and his own daughter Asia, who are able to evoke something like empathetic figures to relate to); but that’s almost beside the point. In some ways, Argento is somewhere on that spectrum of filmmakers who use cinema as invocation, like Kenneth Anger or Alejandro Jodoworsky. While not as provocative or visionary as either, there is something ritualistic in many of Argento’s films. You often feel as though you are watching something forbidden unveil itself before you. You weren’t invited, but you are now complicit in a kind of slow burn of increasing madness.

“Suspiria” may be his magnum opus in terms of everything mentioned here already; but I have to credit “Inferno” with being not that far behind in terms of atmosphere. It falls very short of the earlier film where performances are concerned and the underlying subtext of the Three Mothers (“Suspiria” was the first in the series focusing on the Mother of Sighs; the central figure behind all that transpires here in “Inferno” is Mater Tenebrarum, the Mother of Darkness; the third is Mater Lachrymarum, the Mother of Tears, who appears briefly in the current film and was given a fuller canvas in Argento’s 2007 film titled, appropriately, “Mother of Tears”) feels particularly underdeveloped.

There are some genuinely good reasons for this, not the least of which is that Argento was ill with hepatitis for much of the film’s production, delegating directorial duties to Mario Bava and Bava’s son Lamberto. Argento himself called it the most difficult film of his career to make and yet, I have to confess, there are moments of insane beauty and a kind of loosey-goosey flow that sweeps us along with what is a kind of rickety, not well-thought-out story.

I do not really want to harp on the film’s shortcomings, though. To me, it is a fascinating film irrespective of its flaws, if only because it does feel like a fever dream and as such, it is almost fully realized as the best of Argento’s work.

The plot, such as it is, centers around a young poet in New York - Rose Eliot - who has begun to translate a venerable and cursed alchemical tome called “The Three Mothers”. You do rather get the feeling that a young Sam Raimi drew at least a little inspiration from this (well, the “Necronomicon” of Raimi’s “Living Dead” films has its origin in the writings of H.P. Lovecraft, but I can’t help but feel that Argento’s use of a damned book here served as a pointer for the direction the use of such a device could go.)

Rose is unnerved by what she uncovers and writes to her brother Mark (Leigh McCloskey) a musicology student in Rome. Mark himself, more “grounded”, has an unnerving experience in class when a mysterious young woman (Ania Pieroni, credited only as “music student” but is plainly more/other than that) appears and seems to lure him into trance. It is an odd sequence, but effective when taken on its own. As Mark snaps out of it, he rushes off to pursue the mysterious woman and leaves behind the letter his sister sent to him. His classmate Sara (Eleanora Giorgi) picks up the letter and in one of those odd sequences that seemed to start out as one thing, then changed to another and became the original thing, goes after Mark, gives up and hails a cab and seems to be heading back to her house, but then requests to be let out at a library, though it seemed to be implied she was en route to Mark’s apartment.

It should also be noted that water is a principal motif during this part of the film. The New York sequence had a particularly remarkable sequence where Rose lowers herself into a submerged antebellum ballroom (perhaps? I’ve read it described as such, but it could just be a parlor), in order to retrieve a key (“the key is beneath your feet”; a passage in “The Three Mothers” that seemed to cast a spell over Rose). It is a stunning sequence that defies logic and sets the tone for the more fantastical elements we encounter in the rest of the film. In Rome, the rain seems unceasing and later in the film, another character meets his demise in the run-off from a sewer in Central Park.

Returning to Rome, Sara locates the book and in another motif in the film, finds herself following a labyrinthine passage to sneak out of the library with “The Three Mothers”. She stumbles upon a book spine repairing area which, of course, could equally be an alchemist’s laboratory. There is a tall central figure with his back to Sara who demands her surrender of the book (and her life, or so we may assume). The book he gets, Sara he does not.

Upon returning to her apartment, she begs her neighbor Carlo to come with her and keep her company until Mark gets there. She calls Mark in a panic, explaining that she has Rose’s letter. As happens in any Argento film, Mark is not going to get there in time to have a nice cup of coffee and chat with Carlo or Sara. In a genuinely suspenseful set piece, the lights go out in Sara’s apartment and both are knifed to death by an unseen assailant. By the time Mark gets there, he enters a crime scene and picks up the shredded remains of his sister’s letter strewn on the floor. As he exist the building, he sees a cab pull away with the mysterious music student in the backseat. It isn’t made explicit in the course of the film, but the student is actually Mater Lachrymarum. Pieroni was invited to reprise the role 37 years later in Argento’s “The Mother of Tears” but declined as she felt she had aged out of the role.

Just as a side note, it’s fascinating to me how the police are summarily introduced and dismissed. There is no detective telling Mark to not leave Rome, no moment of requesting him to come to the station for additional questioning, etc. That said, it does streamline the film’s pacing!

Earlier, Rose had begged Mark to come to New York and once he has returned to his apartment, he calls to confirm he will be there, but the call ends abruptly and as the action switches to New York, we see Rose chased out of her apartment and again through a labyrinthine set of passages into a basement or some rather odd place shrouded in cobwebs and with a taxidermied crocodile in the distance on a table. The place, like many in Argento’s films in general and “Inferno” in particular, evokes a palpable sense of rot, though it is visually more in mere disarray than corruption. Nevertheless, there are some deliciously tactile moments throughout the movie.

Recounting how Rose meets her end almost makes no sense in describing it, but suffice it to say that she is grabbed from behind through a broken window where a bottomless frame is used as a guillotine to finish her. This, after having the back of her neck impaled on a nail. As stylish and exaggerated as the murders of each and everyone in this film (and others like it), the executions do carry weight; they are gruesome by inference and more effective for what Argento (and his collaborators) chose not to show.

Mark arrives at Rose’s apartment two days later and we get a greater sense of how genuinely weird the building and its inhabitants are. We are in serious “Rosemary’s Baby” territory (well, we have been, but it grows more explicit as Mark is set upon by truly dark forces embodied by, well, just about everyone.) Of course, as McCloskey plays him - and it could very well be Argento’s choice - Mark is the empirical, rational type but so frustratingly unaware of the oddness surrounding him. In some ways, he is Argento’s Jonathan Harker par excellence. You can almost see him thinking “well, that is strange, isn’t it?” at almost every turn.

From the get-go, he should have figured the joint is full of weirdos. The concierge Carol (Alida Valli) is borderline Nurse Ratchet levels of creepiness. Mark enters his sister’s apartment, the phone still off the hook and in short order meets - deep breath - Elise De Longvalle Adler, played perfectly by Daria Nicolodi, Argento’s muse and collaborator. Quick sidebar: “Inferno” is based on Nicolodi’s uncredited idea for the story as well as Thomas De Quincey’s book “Suspiria de Profundis”). Nicolodis strikes all the right notes: she’s odd, eccentric, vulnerable, and get the idea across that she knows she is not long for this world.

Elise tells Mark that Rose has disappeared and shows him how they communicated via a tube that connected their apartments. In short order, they discover bloodstains and Mark follows them down a flight of stairs into the labyrinth. Elise is understandably frightened at being left alone by and after waiting altogether too long calls for Mark. When he doesn’t reply, she ventures downward into the abyss to find him. Of course, this is a very bad idea. For one thing, we see Mark overcome by some kind of gas or perhaps just a poisonous or anesthetic scent. In any case, Elise sees the collapsed Mark through the window from a slightly higher position. The shrouded figure that brought Rose’s life to an end is seen dragging Mark away but becomes aware of Elise’s presence and initiates his pursuit. She sees this and begins to flee but is soon quickly assaulted by feral cats, cats which have proved problematic to another neighbor whom I’ll get to.

Lamberto Bava directed what is one of the maddest sequences in any horror film I think I’ve ever seen; it is pretty obvious that someone is throwing cats at the actress but it still works since the cuts to exposed fangs and talons does flesh out the idea that the cats are in violent attack mode. But wait! That’s not all! A propos nothing, there is another cut to a cat eating a mouse. A real cat chomping on a real mouse. In fact, I think it’s a three cut shot and on the third pass, the mouse’s bottom half drops from the feline’s mouth. Whew. PETA would not be happy and even though it is forty-two years old, the scene has a visceral repugnance that outdoes the human deceases throughout the movie.

Mark attempts to rally, finds his way back to the lobby of the building where he collapses but not before Carol, the nurse for the mute Professor Arnold give him a liquid and he passes all the way out. Professor Arnold was played by Feodor Chaliapin, Jr., in 1905 in Russia. His father was one of the great operatic basses of the time and whose family eventually had to flee after the revolution. Chaliapin fils stayed in Moscow until 1924 when he emigrated to be with his family in Paris and began working in silent movies. In his later years, he played Jorge de Burgos in “The Name of the Rose” and the kind of addled grandpa in “Moonstruck”. I digress this much on him because if you’ve seen him any role, he really walks off with the scene. Check him out in Fellini’s “Roma” or even for the length of a sneeze in “For Whom the Bell Tolls” (he’s dying in the beginning of the film; I’m sort of half-joking about this.) In “Inferno”, his work is mostly silent but he’s got a great face and physicality.

“The Nurse” is played by Veronica Lazar who was no slouch, either and whose work in humanitarian aid projects might well have eclipsed her dramatic career. The point here is that Argento could call on top flight talent to realize some of the odder characters/elements of his films. He was able to enlist actors he could trust to do the work that might not have been immediately apparent in the script itself and I suspect that this is the main reason why “Inferno” did often work despite Argento’s health issues and other production problems at the time. A strong cast (and in this case, it was mostly the supporting cast) can work wonders with underwritten or merely sketched out characters.

Returning to Mark, who recovers in Rose’s apartment, we begin to get an idea that McCloskey might well have been directed to sleepwalk through much of his role. He eventually meets Kazanian who owns the bookstore that abuts the apartment building and who sold antiquarian books to Rose. In another miracle of casting, Argento snagged Sacha Pitëoff who had a storied theater career (I don’t think there was a major play that he didn’t star in, direct, or produce in Europe from the fifties on) and whose screen work was, to say the least, varied. As Kazanian, he’s a pricky son of a bitch and really, really does not like the cats in the neighborhood.

His discussion with Mark about Rose is short, curt, and dismissive and serves the story less overall than as a set-up for Kazanian’s demise. Once inside his store, he captures an invasive cat and stuffs it in a burlap bag with a bunch of others. In one of the longer and more tedious (and extraneous) sequences, we see the lame man hobble out to Central Park on one clutch with sack in hand trying to find the right spot to sink the kitties. He eventually finds it, but loses his footing and falls face first into the water where he is quickly set upon by rats (well, mice, really, if we’re being honest). He yells for help and eventually, a hot dog stand attendant/cook hears him, grabs a large knife, and fends off the rats to save a grateful Kazanian. KIDDING! He stabs Kazanian to death and no doubt leaves the body for the cops.

In my mind, the hot dog vendor has nothing to do with the plot of the movie and kills Kazanian because he is aware the the old bastard has been drowning cats and has decided to end this once for all. However, of course, that is not Argento’s intention. The idea is that the remaining Mothers are the driving forces behind all this evil on their way to plunging the world into darkness.

It is around this point that the movie loses its own plot and feels increasingly rushed. The atmosphere evaporates from here on as we return to the apartment building where Elise’s butler John has been conspiring with Carol to defraud Elise and steal her jewels. John is murdered, Carol discovers his body and drops a candle which catches a tapestry on fire that she can’t put out and begins to spread.

In the meantime, right next door in Rose’s apartment, Mark (how did he not smell smoke?) unravels the clue about the key beneath his feet and finds a secret passage beneath the floor. Mark discovers Professor Arnold who communicates via a computerized vocoder. Turns out, get ready, Professor Arnold is actually Doctor Varelli, the author of the book “The Three Mothers”! Arnold/Varelli attempts to inject a drug into Mark, fails and through what almost reads as a pratfall, finds himself being strangled by the cable lead from his computer to the speakers. Mark unties him and Varelli tells him that Mark is still being watched. Mark eventually finds a well-appointed antechamber where he encounters The Nurse who - AHA! - is really Mater Tenebrarum!!!! She vanishes and reappears as Death itself, after declaring that the Three Sisters are, in fact, Death. Eventually, the fire consuming the building finds its way to the witch’s layer and collapses on Mother Tenebrarum/Death and gives Mark the chance to escape. He makes his way through the lobby and out into the street and the movie ends with a shot of Mark looking up from below.

Until Kazanian’s death, the film had been doing a fine, tight job of building up an ethereal atmosphere of dread and yes, rot and decrepitude. It lost the thread almost immediately and it was fatal to whatever the film was building to. That said, we have three-quarters of an Argento masterpiece.

His use of color and the elements of water and fire that seem intended to have divided the film into two parts should have yielded a fitting sequel to “Suspiria”. As it is, for the first two-thirds there are some of the most riveting and creative uses of set design, subterranean spaces, and a kind of architectural space that may actually be a psychological space of malignancy that subsumes/consumes the characters.

Romano Alberti, Argento’s cinematographer on this and other of his films, employs a shrewd sense of the lurid. Soft focus that renders some of the nastiest shots like Dutch still lives, color saturation and a use of filters that completes what the set design begins, and framing that seems straightforward until you realize, it’s really not. He uses a lot of rectilinear framing and very few “off” angles but he is keen to ensure that when we gaze into the abyss, the space is very well defined as just that. When he shoots from a lower POV, it capitalizes on the sense of having descended into a region of the mind or the cosmos that might very well be where lost souls go.

Lastly, Argento traded out Goblin for Keith Emerson as composers for the soundtrack and it is a curious, though not unwelcome, change. Goblin as a band inhabited that Popul Vuh/Tangerine Dream area of electronic prog soundscapes that generated both atmosphere and propulsive rhythmic doom. Much of Emerson’s score is lush, symphonic, and nicely atonal by turns. Unlike a lot of people, I really like it. It could well stand on its own as a symphonic suite but I didn’t find it intrusive or distracting; I thought his work like Alberti’s visuals supported the story quite well.

After watching “Inferno”, I felt like I had gotten more than I expected. The eighties are the turning point for Argento as in “downturn”. There are still strong films to be had, but nothing like his seventies output and in more recent years, the results have been spottier.

I have a huge hankering to revisit “The Bird with the Crystal Plumage” and “Deep Red” (I feel like I just saw “Suspiria”; I watched it before Luca Guadaguino’s excellent remake/reinterpretation). Despite Halloween having passed, that won’t stop me from doing so.

The worst that can be said about the variable quality of Argento’s oeuvre (like Fulci’s or Rollin’s) is that it can grow wearisome. Not necessarily boring; just frustrating. His sense of pace and choices in the editing bay don’t, frankly, make a lot of sense. Even given the oneiric nature of his work, there is often a fraying at the seams.

To be sure, given his best work, he remains a master of the genre and that’s not a title that can be taken from him. With each new release, there is an anticipation that he will produce a return to form and grace the horror world with one more masterpiece. He has a unique vision and when it works, there are few who can match him. While he works within gialli conventions, he seems determined to push the boundaries of just what those boundaries are and for that, he should be lauded. Even when the individual works don’t measure up to his earlier work, they remain identifiably Argento.

Comments

Post a Comment