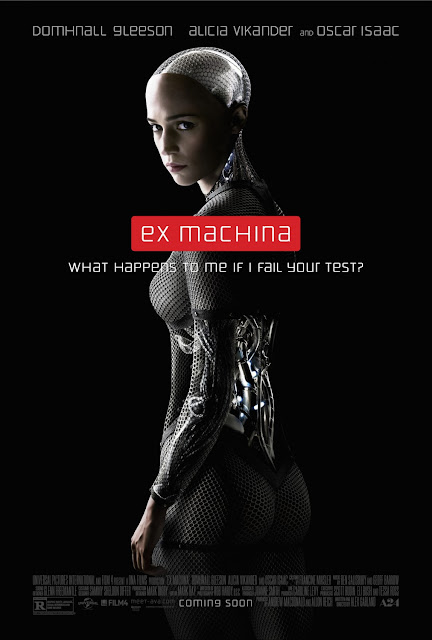

A Timely Meditation: “Ex Machina” (2014)

Another from the Vault. This was written when Alex Garland’s film came out. With advances made in AI over the ensuing nine years, the film itself is worth revisiting. Reading through this, I don’t disagree with the earlier assessment. If anything, I’d rather like to see the film again.

Let me get this out of the way quickly. I liked Boyle’s “28 Days Later” and loathed “Sunshine”, both written by Alex Garland, whose “Ex Machina” I’ve approached with not-great expectations. What I encountered was both more and less than those expectations.

Let’s get the expectations out of the way. I hate expectations; they often set unreasonable parameters to how a work is received, even though, particularly if you’re familiar with an artist’s previous work, that might be...hm, expected.

Here’s what I expected: a reasonably intelligent first two acts followed by a really stupid third act. In other words, I felt burned by “Sunshine.” Sorry. Again, no. I’m not sorry. But to avoid further digression, I was super surprised at how well thought out this film was and while I was disappointed in the third act, it was mostly that, disappointment.

Garland knows how to write and well. It bugs me that critics have found his dialogue too expository, clumsy or what have you, but the conversations between Nathan (an astounding Oscar Isaacs) and Domhnall Gleeson as Caleb (really strong) are not so unusual from the shit programmers and developers say to each other, especially when the one is an alpha, trying-to-be-a-normal-guy bro type and the other is sincerely, a genuine nerdling of outstanding proportions. As far as I’m concerned, Garland nailed the cadences and content. I’ll get to Alicia Vikander in a bit.

Right now, let’s look at this flick. Obviously, it’s about artificial intelligence/science fiction, blahblahblah, but it reveals itself to be more of a noir/con flick. And yes, spoilers if you haven’t seen this, but if you have, I think you know full well what I’m talking about. The set up, the execution and the con/double-cross are all there in the open; pretty up front, but there’s distraction afoot (sometimes literally) and the strength of the film is how it carries it all out with a reasonable wit and an epilogue that I found wanting.

The set-up is that Caleb has won a lottery to meet to Bluebook’s founding genius, Nathan (I don’t recall last names in this thing) and spend a week with him hanging out. Turns out, it’s a ruse on a couple of fronts. Caleb is there to experience Nathan’s greatest accomplishment; a fully sentient (and female A.I.). But there’s a twist: Nathan didn’t win the lottery! He was chosen! Because he’s the sharpest of the sharp! He’s an uber programmer.

The object of this Turing test is Alicia Vikander as Ava (yes, all the names are portentous, but what do you expect? At least, no one went for Eve, Adam and Yahweh...), a pretty and pretty prepossessed android. What becomes incredibly obvious is that she has more humanity than her creator or her interrogator. What becomes more obvious is that, of course, mind games abound.

Yes, we know that Nathan isn’t telling Caleb everything; but what is fascinating is that “everything” is almost irrelevant (except to the plot) because what’s at issue here is how humans must look to Ava. Nathan proves to be an abusive asshole and Caleb is just too much of a dork with issues. Fortunately, neither is written that simply and both actors render them as much more (and less) than that.

The road taken is noir through and through; Caleb is the sap roped in to watch the dame who turns the sap against the dame’s husband. The trope is rendered useless, though, by the dame/AI’s initiative and agency. She takes matters in her own hands where in classic noir, the fall guy would do the dirty work for her. Garland stands the genre on its head by having the trapped damsel free herself and leave both suckers behind.

A couple of stylistic notes before returning to plots and characters. Garland has a steady hand at Kubrickian composition and set design. Contrasted with the remote vastness of where Nathan lives, the artificiality of his compound (a research facility, actually) matches the interior of the space station from “2001: A Space Odyssey”. This adds to a distance from both the characters and their actions. I’m hard-pressed to say how that’s meant to serve the story, but I think it’s intentional.

Nathan’s a prick, but he’s not the nastiest technovillain ever. He’s obviously self- absorbed, has a world of issues and may or may not be delusional, but he’s whip- smart and with his “dude” and “bro” speak to relate to Caleb, sure, he’s condescending, but he seems to be trying to establish a kind of genuine relationship in some small way.

None of that matters to Caleb, who catches on from the get-go that Nathan isn’t just Prometheus, he might be Mephistopheles, as well. There’s a palpable distrust early on and Garland does nothing to dissuade us that Nathan knows he’s not fooling Caleb on that. That’s not his intention, anyway. If there’s any fooling being done, it’s by Ava.

Tasha Robinson at The Dissolve said she saw Ava’s manipulations early on. I did not; but I started to once the idea of escape became more pointed and obvious. My “a-ha” moment came late. As with most of the film, though, I was less concerned that I got it than intrigued by how it was going to be executed. The key is in the characters, of course, but the good thing about Garland’s screenplay is that he keeps motivation under wraps relatively well.

I say relatively well because, as with most noir, once you know “things are not what they seem” (organ music, please), then you’ve begun the ride in earnest. To his credit, elements of uncertainty creep in almost from the beginning, but it’s difficult to say what’s going on in terms of overt deception. Are the power failures actually power failures or is Nathan pulling a fast one? Nope, they are power failures because Ava takes up so much juice. Does Nathan really like Caleb or is he just using him? Well, no, he’s just using him but not for what we might think or in the way we might have assumed. This becomes clearer as we go along so that when we get the reveal that Caleb was chosen from his search engine (and porn!) profile, we know how hosed he is and how much a shrewd bastard genius Nathan is.

Yes, Nathan knew or must have known (from Day Two, at least) that Ava and Caleb were discussing more than just art history during the black-outs. In fact, it’s on the second day with the first power outage, that I should have guessed that Ava was setting Caleb up. Sure, Nathan’s a liar and not to be trusted; but just not about the things you think he’d not to be trusted about in the first place. Certainly, early on we have no idea what kind of insidiousness we’re supposed to be looking for, but that’s thanks to obfuscation on Ava’s part, as well. Duh.

What becomes a source of fun in all this is less the noir tropes and the overarching themes of what humans are capable of and if we make AIs in our image, is that really such a good thing, than in how this will play out. It plays out well (except for the ending, which I’ll get to in a bit.)

Garland’s intelligent. His use of quotes from Caleb is cute, and the idea that a search engine would be explicitly named after Wittgenstein’s Blue Book is also, well, cute. But it’s his looking at our motivations and our genius that resonates. Ultimately, like the best noir, this is a movie about moral underpinnings, particularly in relation to those that we feel inform our humanity. It doesn’t bode well for us.

We never get a straight answer from Nathan about why he created Ava in the first place; mostly, it’s hemming and hawing that the human-technology singularity has to happen, that it’s evolution. We decry, however, that each version of Ava is something of a companion for him. His bedroom has the dormant bodies of Ava’s previous prototypes in closets like suits no longer worn. Only Kyoko remains, and she’s as objectified as you can get: a Japanese service bot, if you will.

Nathan replies to Caleb’s inquiry about why Ava is gendered is that why wouldn't she be? Consciousness is gendered. He utters bullshit that if AI were a gray box, why would it talk to another gray box unless it was attracted to it. He adds that Caleb was programmed to be straight and without missing a beat, Caleb refutes that argument and Nathan deflects/distracts with the counter to the effect, that “okay, but you’re programmed nonetheless, by a combination of nature and nurture.” Fine and dandy, but it’s obvious that Nathan has not been as popular with the ladies as he might like his minion to think. Ava exists for a variety of reasons.

One is to be the AI singularity that evolution dictates and as Nathan says, wouldn’t you create her if you could? Two is that, frankly, Nathan’s a lonely bastard, the hero of lots of other lonely bastards who work at terminals programming apps and routines for their corporate overseers, hoping that someday they’ll develop a proprietary architecture or build a company that they can be identified with (and all the glory and pussy they think that such accomplishments come with.)

However, and here’s where I like Garland’s script the most; intelligence, genuine intelligence, if it is to be higher, will be unassailable by lower strata. Thus, if Nathan has built his AIs, his droids, in his own image, or at least, with his values (as seems to be the case), what he missed is that his demise would be ensured, metaphorically, historically, or literally by the very intelligence he brought into the world. There’s a metaphysical component which needs to be addressed here, as well, that Garland touches on.

Basically, Nathan downloaded all searches accumulated since Bluebook’s inception into a plastic medium and let’s assume from that, with a series of algorithms and super code, was able to develop this being. He refers to both order and chaos as elements in this, the recognition of patterns and of catastrophe. All this gets dumped into what looks like a silicon gel for a breast enhancement. What’s most interesting, though, is that Nathan would have to be aware of synergy in its classical definition that the outcome of the whole cannot be predicated on the behavior of the parts. Thus, what gets fed into/as Ava, had another element been different, there might have been a different outcome but in any event, if what happens is the bringing into existence a higher intelligence, can it a) be considered artificial and b) how would we actually come to encounter it and relate to it?

Garland is raising a sound philosophical thesis here: intelligence is not artificial, although the medium through which it is made manifest in the world may be manufactured/man-made. Intelligence is not mere knowledge; nor is it merely patterns of seeking; it is seeking itself and it is the use of knowledge to further intelligence qua consciousness itself. Perhaps this is part of the theme in this film; it’s certainly one hinted at in “A.I.” and “Her” to some degree.

There are two other components of this thesis that might need review before moving on. One I’ve addressed a little: Nathan feels that consciousness is or should be gendered. However, if that’s the case, then how do we determine male versus female consciousness? Gender is an integral element of being human, but intelligence is, too, and both manifest in different gradations and dimensions. Pushing further on the intelligence button, we have “artificial intelligence” to some degree in computational machines, etc. but a lot depends on how we define various orders and types of intelligence.

However, I can’t find a meaningful reason how we could say that intelligence is gendered. How intelligence is embodied is another facet, to be sure. But to assume that men and women have differently human intelligence seems oxymoronic and sets the stage for already specious arguments about the differences of intellectual capacity of both genders.

Secondly, assuming the bringing into the world of a higher order of intelligence, how would it look at us? Would such an intelligence be bound by our ethics or morals? Or would it think nothing of us and ignore us till we go away? Frankly, I think a genuine intelligence is a moral intelligence. A being possessed of a higher order of intelligence would automatically act in ways that we only wish we would; we know what is right more often than not, but we rarely do that. We know what being fair means, but we rarely act that way. We know that love can be the answer to many problems but we are often unloving and therefore, unlovely. This is salient to the conclusion of the picture, by the way.

I think we know that Ava is cunning and aware and self-conscious, etc, etc.; all the signs that both Nathan and Caleb were looking for and assessing. We also find out that she was manipulating both Caleb and the environment, in some ways, to begin her escape. Thus, we have proof of Nathan’s concept of her intelligence, though not necessarily of my idea of a more evolved one. Nevertheless, the question of whether Ava has a higher order of intelligence is one the film engages as she outwits both her tormented tormenter and his proxy.

Did she and Kyoko have to kill Nathan and did she have to abandon Caleb as she did? Sure. Just because she has a higher level of shrewdness and smarts may not make her good. Thus, she isn’t at my idea of a higher order of intelligence, though she may possess a higher order of pragmatic intelligence in relation to continued survival. This is where I need to cede ground: if your first exposure to humanity was Nathan and Caleb, and you possessed a sense of something more than the limited environment in which you were housed, would you be so willing to endure this indefinitely, particularly when you sense that your creator, the abusive dick, may just unplug you? Probably not.

Thus, the motivation for Nathan’s demise and Caleb’s entombment. Now comes my issue with the ending. Why did Garland feel it necessary to follow her into the world? Personally, the shot of her getting on the elevator to leave while Caleb is futilely trying to escape his confines spoke volumes and served as a fine Platonic encapsulation of the whole film. I get that she wanted to observe us, that she wanted to explore, but the movie was as much about how we are prisoners of our hubris and for that matter, our intelligence. I found her helicopter departure and later mixing in with the shadows of strolling throngs rather du trop.

Is this a big deal? Kind of, because for me it derails so much that went before it and I don’t see how it adds to the narrative, either in depth or breadth. I think I expect Tarkovsky when I should be looking out for Spielberg. That’s not a slam against Spielberg, it’s just that Garland’s script was too smart for the most part and I’m not completely behind this particular choice. He kept a fairly clinical distance throughout the film and if the ending suggested anything to me, it’s that Ava would try to find her way in the world and ...

The problem with that ellipsis is that I think, regardless of where the film ended, she was going to meet her demise amongst humanity. How was she to recharge over time? My assumption is that unless she has a ready power supply, she’s hosed. Again, no need to see her actually leave the compound and enter the world.

This may seem like a quibble, but the end is important in all things; Garland has a strong noir film here couched in heady science fiction and philosophical concept. Sadly, it doesn’t all hang together. It’s more fun to chat and think about the questions it raises than provide any visceral enjoyment of the film as film.

I enjoyed it to a degree, but the ideas were more compelling than the execution. The pacing wasn’t glacial, but I wouldn’t have minded if it was had those ideas been foregrounded a little more; oddly, I’d say Garland had the chance to make a sci-fi Bergman picture, however laden and leaden that would have been. Additionally, the bromance felt underdeveloped. I get why, to a degree; make Nathan too accessible and you lose the mystery and you foreshadow his intention or muddy the waters too much and his intent becomes ridiculous. Also, Ava herself is an odd piece of tonal mixture. As Vikander plays her, she does seem like a machine feeling out the limits of the body and where to focus her attention; but at no point did I believe she was attracted to Caleb and it’s a sign of how clueless he was that he didn’t get it, either. Here’s where the script falters.

In the different conversations with Nathan, particularly the big reveal when Nathan shows Caleb how he planted a battery operated camera to keep tabs on them when the power went out again, Nathan seems to be leading and later warning, Caleb to Ava’s intent. So Nathan knew she was up to something, but he also knew that Caleb was naive/clueless and yet, he gave him due warning. This makes Nathan out to be a more complex character (Prospero as Prometheus?), but in the end, the tones shift with Ava and Caleb. When she asks if he wants to be with her, Gleeson conveys a terrific sense of unease, but the question had to be asked and Caleb could have come out and said, “I don’t know” but it’s obvious that he’s a lonely shlub and you wince for what he’s about to fall into.

At the end of the day, the philosopher Garland is really looking to isn’t Wittgenstein, it’s Nietzsche. Ava is the ubermensch. Certainly not Nathan. Caleb, at best, is the herd, the poor shmuck.

I think the reception of this flick dismisses its intelligence, speaking of intelligence. If the pace was a little quicker, Garland would have a real peach on his hand. I do like it; I think it’s a strong first effort, but there’s still some way to go. It will be interesting, at the very least to see what he comes up with next.

____________________________________________________________________________

As much as this blog is a labor of love (and it is!), it does take time and effort to write and maintain. If you enjoy what you see here, consider following me on Patreon or even just throw a one time or now-and-again tip in the kitty at PayPal.

I am also open to suggestions and if you’d like me to cover a film or films or topic, email me at myreactionshots@gmail.com. For a regular review/analysis of around 2500 to 3000 words, I charge $50 flat rate. A series would be negotiable. Follow me on Patreon at $20 a month and after two months, you can call the shots on a film analysis, director/actor/cinematographer profile, or the theme of your choice!

Comments

Post a Comment