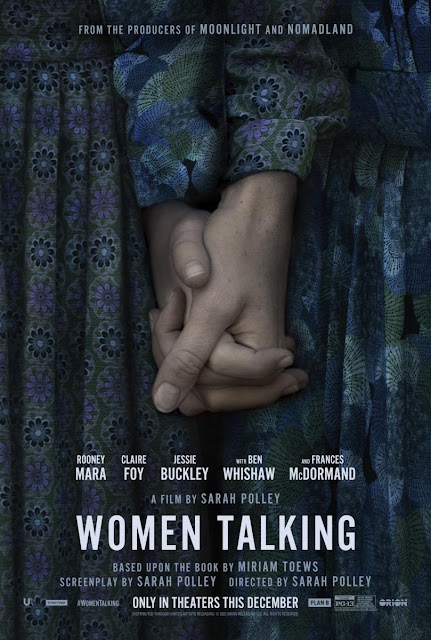

Listen: “Women Talking” (2022)

It’s difficult to overstate how timely (and sadly, timeless) Sarah Polley’s adaptation of Miriam Toew’s novel is. Despite being based on a true event - the systematic drugging and rape of women members of a Mennonite cult group in Bolivia - the current framing is of a discussion based on and surrounding women’s agency and the oft-uncomfortable intersection with faith and often male-led religious institutions. It is a necessary and moving conversation.

The film opens on a woman in bed, asleep with visible bruises and wounds, a voiceover tells us that they - the women of this community were merely tools of the devil, or ghosts, or simply lying to get attention, or “an act of wild female imagination” - but that one of the attackers was caught and he, in turn, named the others. The the men have left to post bail for the assailants, giving the women two days to forgive the attackers before they return.

However, knowing that these attacks were not the work of Satan or ghosts or the results of “wild female imagination”, the remaining women have appointed a group (task force?) to come to a decision for the next moves, when an earlier vote resulted in a deadlock. The options are to do nothing and stay in the community, stay and fight, or leave.

That is the plot. It is simple and straightforward but the dialogue that ensues is anything but. There are passionate and often nuanced reasons put forward for each option; however, what becomes readily apparent is that Polley is contextualizing these options as a direct response to a ruling patriarchal hegemony. Though set in a community at a remove from contemporary society, those options now come across as viable alternatives to the oppression of women in any number of societies, not the least of which, would be in the United States itself where women’s voices are increasingly marginalized and access to healthcare and abortion has been substantially reduced, if not effectively removed.

The decision to stay and leave whatever happens (likely more abuse and no doubt, retaliation from the men) to God is Scarface Janz (Frances McDormand)’s stance. She is an elder who surely must have been aware of decades of similar behavior. But her fear is that in leaving they will be excommunicated and refused entry to Heaven.

The remaining options require more discussion and analysis. Staying and fighting finds support by Majel (Michelle McLeod) and Salome, both righteously angry who have been either raped (Majel) or subject to vicious spousal abuse (Salome). Ona herself believes that staying and fighting and changing the power structures of the community is best route. They are matched in passion and commitment to Mariche (Jessie Buckley) who advocates for staying and working from a place of forgiveness.

All the women in this single set (for the most part) film are present with an honesty not very often seen on screen. Each voice is distinct, each carries weight. From the two young girls Autje (Kate Hallett), Mariche’s daughter and Neitje (Liv McNeil), Salome’s niece to the two elders Agata (Judith Ivey) Ona and Salome’s mother and Mariche’s mother and Majel’s aunt Greta (Sheila McCarthy), there is no wasted verbiage and every word counts.

The setting is a loft in a barn and Ona has enlisted August Epps (Ben Whishaw) to take minutes and note the pros and cons of the different options. As the sole man (more on Melvin later), August is very much a listener. His parents were exiled from the community years before and August attended university and returned to teach the boys. Girls are not taught to read or write; hence, August’s presence. This is not to say that August is without voice; he has the good judgement to recognize that this is not his place to speak.

August was contemplating suicide when Ona calls on him and we do understand that he is very attracted to her, but over the course of the discussion, we also quickly see (as does August), how trivial that appears in the face of what is before him.

As much as “Women Talking” begins centered on rape, it brings in the greater contributing factors that lead to it; specifically, the power and privilege of men over the women in the colony, but by extension, in the wider world. The colony is very much a microcosm that renders the uncomfortable truths of contemporary more intimate and I hope, for many, even more uncomfortable.

We can zoom out further and question the nature that faith or religion plays in the matrix of society, as well. Is a forced forgiveness really genuine? Salome avers that she will never forgive the men for what they’ve done. Ona is more of a visionary and believes that change can come, particularly if there is transparency and accountability. It is she who ask, “Is forgiveness that’s forced on us true forgiveness?”

Moreover, the question also implicit is who gains from mere forgiveness if the forgiven continue to perpetuate gross injustice on the forgiver.

As for faith, Scarface Janz exits early on when it becomes clear to her that the discussion may not settle into a simple matter of returning to the status quo to ensure a place in the Kingdom. Indeed, even that is brought up when the question arises about the how would the women be found were they to leave? Salome figures that given Jesus’s abilities, “surely he’d also be able to locate a few women who left their colony.”

However, we go deeper than that. The women tease apart the very structure of the system that gave rise to and perpetuates the toxicity; is it possible that the men themselves are victims of that system and are, ultimately, innocent and worthy, again, of forgiveness?

All of this might sound too talky or stagebound, but I assure you, it is gripping and even leavened with humor. The women take breaks (including Majel, who refuses to be judged for smoking; a vice she picked up after her rape) and the young girls are a Greek chorus of impatience until they, too, eventually grasp what’s at stake.

The point at which it becomes more of the moment to leave is initiated by another consideration of forgiveness as permission. It was Greta who influenced Mariche to forgive her husband. There was repeated abuse there and as Greata says, “what you were required to do was a misuse of forgiveness.”

The effect this has is subtle. There’s no “aha!” There is the recognition that it is unlikely staying, much less staying and forgiving, is going to result in much more than a continuation of the way things have been. Similarly, the idea of staying and fighting loses its luster, as well.

This latter comes through a discussion of the articles of a faith that abjures violence (well, at least, for half the population’s use), but is genuinely expressed in the words and actions of the women before us.

The three main - and compelling - reasons to leaver are enshrined in August’s notes on a large piece of paper: the safety of the children lands first. Earlier a question arose and was put to August about when did boys develop the capacity to become abusers and can they be guided away from it? The decision is made to take the boys fifteen and younger, but no boy over twelve would be forced to come.

Remaining steadfast in their faith lands as an authentic and deeply felt motivation. Staying would result in a situation of probable discord, if not outright violence on a terrible scale, and even were that not the case, the destruction of the soul’s peace on everyone’s part, appears to be unconscionable. At first, I interpreted this as a kind of capitulation, a fleeing from the responsibility to see justice done. However, I realized that wasn’t the case (and was really starting to sound like Salome from earlier in the film; had I learned nothing?); leaving the colony was not turning their backs on God but perhaps a way for growing closer to Him by reducing the exposure to further harm and ill-will. Perhaps this would even lead the men remaining to reflect on, question, and change their ways.

The third reason: freedom of thought. This is not writ large; but it is obvious that throughout the film’s running time, what have we been seeing but the exercise of that very freedom. Perhaps for the first time in their lives, these women have been able to express themselves freely and honestly.

Once the decision has been made, Melvin arrives to alert the women that Klaas, Meriche’s husband is returning to get more money for bail. Melvin was originally Nettie, who was also raped and transitioned to assuming a male identity. Nettie, upon becoming Melvin, ceased to speak, except the youngest children. When he arrives at the loft, he utters words but only because Ona (I think? I really don’t remember as I was taken by surprise) asked him to speak. Later, Melvin thanks her for using his name.

The next day, we see almost the entire female population leaving for exile into the greater world. These women who had never seen a map are given one by August who shows Ona how to use celestial navigation and she, in turn, shares it with others.

Did I say “almost the entire female population”? I did. One of the final shots is of Scarface Janz’s daughters leaving her to joint the caravan. There is a kind of forlorn understanding in McDormand’s eyes and I think I understood both her decision to stay and the toll it will take on her; but in that, I suspect she felt a greater toll would be taken on her daughters if they were to remain behind.

Mariche and Autje have been beaten but join the group and Salome has taken the extreme measure of drugging her son Aaron to bring him with them. August swears he’ll tell no one (and has also given her the gun with which he contemplated ending his life, for protection) but asks that she look after Ona.

Ona does cast a look back and it’s unclear if August can quite make out individuals at a greater distance. He stays behind with the mandate to educate the boys to end the cycle of patriarchy and the legacy of abuse.

I have not gone into the performances, the camera work, the score, or any of the more technical aspects of the film because this is a story that needs to be seen, shared, discussed. It is far less of a difficult film to watch for any visual dramatic or disturbing imagery than for the simple fact that what these women are talking about is what we should all be talking about and more, addressing through our actions, as individuals and as a society.

It has been opined that we are reaching “peak #MeToo” in film with works like “She Said”, “Bombshell”, and “Women Talking”. Arguably, we could also add “The Woman King”, “The Assistant” and others, but the idea that this is a fad or some merely timely movement is missing the point. The #MeToo movement needs to stay around until discussions like this are no longer necessary, until the actions that demand these discussions no longer occur.

One note about Luc Montpellier’s cinematography: Polley used a faded degree of color grading to capture “a world that had faded in the past.” It does evoke a sense of a bygone era of old values; the grading and color values grows sharper even with the aerial perspective as the group is leaving in the last few minutes of screen time. Again, nothing overt or obvious, just enough to let you know that we can move into a new world.

Click here for my Oscar Post-Mortem.

____________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________

As much as this blog is a labor of love (and it is!), it does take time and effort to write and maintain. If you enjoy what you see here, consider following me on Patreon.

I am also open to suggestions and if you’d like me to cover a film or films or topic, email me at myreactionshots@gmail.com. For a regular review/analysis of around 2500 to 3000 words, I charge $50 flat rate. A series would be negotiable. Follow me on Patreon at $20 a month and after two months, you can call the shots on a film analysis, director/actor/cinematographer profile, or the theme of your choice!

Comments

Post a Comment