30s Hitch: The Thriller Sextet

Having completed and suffered the twin humiliations of Waltzes from Vienna and the critical and box-office failure of Rich and Strange, Hitchcock found a new lease on life out from under the foundering British International Pictures. What happened next wasn’t just a restoration of his reputation but a leap forward into the Hitchcock that would find his full flowering in Hollywood with newer technology, larger budgets, and a broader stable of actors to choose from.

If I’ve devoted more time to the pre-Thriller Sextet (Donald Spoto’s coinage), it’s to point up the contrast of what a Hitchcock following his instincts in a more challenging genre would look like against one that was under contract and had to work in a proscribed environment. We’ve seen what happens when a director gives up, cedes power and/or hope, or just capitulates to the demands of producers or the masses. At the same time, we’ve seen how Hitchcock could employ his ample and sure talent to - in contemporary business jargon - “deliver product” and for the most part, do so with some aplomb and panache.

As we enter the back half of the decade, the themes and what would be recognized in his later career as obsessions will become more readily apparent.

There are plenty of reviews available to gauge the reaction to these works and of course, Hitchcock comes more alive in his later interviews once this period is covered. I find it interesting that, like Welles, Renoir, Huston, and Ford, Hitch’s more recognizable-as-Hitchcock films share stylistic details that mark them as the work of a singular, authorial voice. This leads me to consider the merits of whether Hitchcock is or should be regarded as an auteur.

Before I go into that, I want to ask why it matters. Auteur cinema was a term employed by the French New Wave critics to delineate directors who were mostly the authors of the screenplays of their movies, who very often oversaw the cinematography, the editing, and so on. Andre Bazin and later, Francois Truffaut and others at Cahiers du Cinéma championed the notion of the director as author.

This doesn’t always hold true. Prior to the rise of auteur theory, people attended “a Marx Brothers movie” or “a Cagney flick” or “a Randolph Scott oater”; movies were associated with the stars. Of course, there were auteurs since the beginning of film, but the reason it matters is because it is easier to come to terms with the films on the merits of the authorial voice. For all their popularity, nearly none of the superhero films currently popular are necessarily works of authorial choice. Even where unique directors are engaged, it’s difficult to make a claim that those are the driving forces behind works that tie into a broader fabric of story-telling as evinced by the rise of these “connected universes”. It might well be that the latest Dr. Strange film is directed by Sam Raimi, but in terms of how much of a Raimi film it is is opened for debate; similarly with Chloe Zhao, Taika Waititi, and others. It might be that Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy, James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy trilogy and Suicide Squad, and yes, Zack Snyder’s entries in the DC Extended Universe are works of auteur cinema, but for the most part, the genre has the impositions of the marketplace to deal with, these works included.

That said, each of these directors has a unique signature, something that defines their work and sets it apart from more anonymous studio work. It was this that Hitchcock was growing towards and that we see now and again through his silent era work like The Lodger, Blackmail, and yes, in The Manxman; we have caught glimpses throughout the nineteen thirties films, as well, and I hope that I’ve been able to underscore some of the thematic and cinematographic techniques that make the early thirties’ Hitchcock recognizable as the same auteur who will eventually usher in Rebecca, Rope, Strangers on a Train, Vertigo, and other works.

Additionally, it needs to be mentioned that Hitchcock himself wasn’t necessarily regarded as an artist until the French critics took him up as a serious director to be mentioned in the same breath as Welles or Renoir (and Hawks, Walsh, etc., etc.). It is fairly well-known that Hitchcock was more often perceived as a “mere” entertainer (even by himself) and that he was frustrated and stung by the indifference, if not rejection of his more personal works like Rich and Strange, Under Capricorn, and even the earlier Manxman.(1)

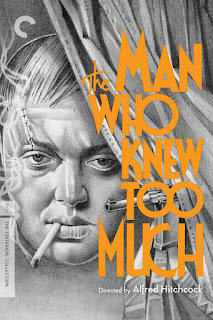

Nevertheless, a genuine of appraisal of his work and elevation of his standing as one of cinema’s greats did take place during his lifetime and it is with The Man Who Knew Too Much that we begin in deeper earnest to examine “30s Hitch”.

Note

“Alas! Though the film was a marvelous artistic success, it was a resounding commercial failure. British critics who had praised The Skin Game to the skies (good God, why!) greeted Rich and Strange sulkily and spoke of an abrupt decline. There was evidently no appreciation of fantasy and audacity in English film circles, and the movie didn't make a penny.

“This failure unquestionably affected Hitchcock. There is some- thing paradoxical about the fact that this popular film director ever managed to get his most daring, his most candid, works accepted. The failure of Rich and Strange, like the later failure of Under Capricorn, undoubtedly prevented him from continuing along a path that he nevertheless knew was promising. If we consider Hitchcock's overall career until now [1957], it immediate- ly becomes apparent that all his films tend to blaze or consolidate a new trail, and that just when things are about to take off, a commercial failure checks his klan and forces him to look elsewhere. His most sincere works, such "pure films" as The Manxman, Rich and Strange, Under Capricorn, and most recently The WrongMan, were culminating efforts, whereas to Hitchcock's way of thinking, they should have been points of departure.” (Rohmer and Chabrol, pp. 35-36)

Bibliography

Rohmer, Eric and Chabrol, Claude. Hitchcock: The First Forty-Four Films. Frederick Ungar Publishing. New York. 1979.

Comments

Post a Comment