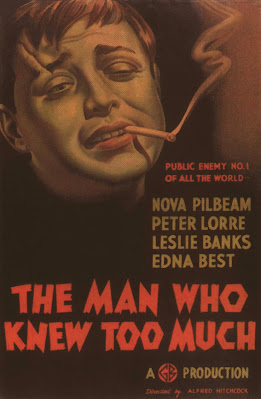

30s Hitch: The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934)

The move to Gaumont British Picture Corporation (just “Gaumont” from here on) afforded Hitchcock a larger, more sophisticated canvas and the first movie was a righting of wrongs and a genuine “told you to so” to one producer specifically. More than that, though, The Man Who Knew Too Much is a template and manifesto of the films to come. In its brisk run-time, it seeds the screen with a number of themes that Hitchcock would explore in greater depth with increasing assurance over the coming decades.

It’s a delicious little film that practically demands you watch it again. I use the word “economy” a fair amount. A 75 minute show can feel stuffed to the gills with wit and profundity and be over before you know it. Or it can drag on ridiculously to the point of taxed patience or sleep. A three hour epic can fly by, and so on. Here, Hitch has brought us an instruction manual of how you direct a fleet, witty, and even provocative film in under an hour and a half, handily.

Edna Best and Leslie Banks play parents of Betty (Nova Pilbeam) on vacation in St. Moritz. Best’s Jill Lawrence enters a clay pigeon shooting competition, but loses and blames Betty for distracting her, unfairly. She loses to Ramone Levine (Frank Vosper), who is later revealed to be a member of a terrorist cell lead by Peter Lorre in his first English speaking role. In the Hitchcock universe, we get our first glance of the retribution for sins committed against the innocent.

For such a brisk, short film, there’s a slow-burn build before the action kicks into gear. The dialog is brisk and easy as the Lawrences have made friends with Frenchman Louis Bernard (Pierre Fresnay, incredible in La Grande Illusion three years later and here, gentle, reserved, and debonair) and the ensemble coalesces in as unforced manner as any drawing room comedy might.

At a dance that evening, Louis is dancing with Jill (Best) and Bob and Betty conspire to play a trick on them when they attach a hanging thread of yarn from a sweater Jill was knitting. As they dance, the sweater, of course, unravels, but it also becomes something of a web ensnaring the dance floor. There is no gunshot; Louis is stricken silently in a sequence so smoothly edited that it is but one moment that puts a lie to Hitchcock’s assertion that the earlier version of The Man Who Knew Too Much was the result of a talented amateur.

The camera pans to the bullet hole in the window pane and is encircled by an overlay of hands pointing to it, no attention is paid to the fallen Louis except that he passes a message to the Lawrences that there will be an assassination attempt on a visiting head of state at the Royal Albert Hall. Bob retrieves the note hidden in Louis’s shaving brush but by that time, Betty has been kidnapped.

Any sense of slowburn has now vanished, but in keeping with the very Englishness of the Lawrences in Switzerland and later, of the remainder of the film, there is a sense of a proper pacing of the action. Louis was working with the British Foreign Service and when they approach the Lawrences, find themselves somewhat stonewalled as both Bob and Jill deny knowing anything of what Louis was working on. This is seen through plainly by Gibson (George Curzon) who presses the issue to obtain the Lawrences’ compliance, “Because one man you never heard of killed another man you never heard of in a place you never heard of, this country was at war.” Hitchcock is often seen as an apolitical filmmaker, but I don’t think it’s missing the mark to say that he was shrewd enough to recognize patterns of causality between politics and violence. It may not be central to his oeuvre, but it is a feature that cannot be discounted.

I remarked earlier on his takes on class when looking at Juno and the Paycock, The Skin Game, and to a lesser degree in Rich and Strange, but it’s here where Hitchcock’s canvas broadens to take in geopolitics that we sense lives threatened less by class structure and societal entanglements than by the winds of history and the effects on daily life these winds have. Both Hitchcock and British cinema had to be acutely aware of what was transpiring on the continent and the rise of the Third Reich in Germany was too chilling to be ignored; the not so distant memory of what happened in Sarajevo coupled with the rise of National Socialism in then current provided a springboard for Hitchcock to expand the context the more intimate struggles would take place in.

We’ll come back to this in The 39 Steps, Secret Agent, Sabotage, and The Lady Vanishes, but it’s worth keeping in mind that Hitchcock didn’t work in a vacuum. The world provided plenty of narrative elements for context, while he also deepened his use of psychological subtext.

From here, the Lawrence’s take matters into their own hands. Enlisting his friend Clive (Hugh Wakefield), Bob is able to find a lead to the gang’s whereabouts. In one of the most economical scenes in an already economical film, Bob impersonates a dentist and is able to pass undedicated at the gang’s headquarters. But he still doesn’t know precisely where Betty is being kept.

The only thing keeping Betty alive is the message on the piece of paper which contains the time and place of the assassination. The Lawrences prove resourceful and Bob and his friend Clive are able to trace Lorre’s Abbott and his gang to a sun-worshiping cult’s temple where they are uncovered and one of the best action sequences in early English cinema plays out. Clive and Bob throw chairs and punches and have chairs and punches thrown at them; it’s a well-choreographed display of borderline Monty Pythonesque anarchy in one of the most tightly

structured films of the time.

It’s here that I really question a number of Hitch’s own critiques about this film. For its time, it’s head above shoulders more accomplished than many of its ilk even by Hollywood’s standards. He said it was structurally messy, but I find that difficult to support and if anything, where some might see something unpolished, I’m reminded of something Yacowar wrote, that these thrillers are “fantasies of varying remoteness from reality”; this has been a key element for me in revisiting this sextet of films repeatedly. Hitchcock said that the British audiences were more accepting of narrative stretching and bending, if not the outright dispensing of logic (“Logic is dull; you always lose the bizarre and spontaneous.”)

Is it not as polished as the 1956 remake? Of course, but as a tight and taut work of suspense, it’s very much the latter’s equal. At no point do we lose sight of what’s at stake; there is a family coming to grips with their daughter’s abduction and possible, probable execution at the hand of a gang of terrorists and we have the possibility of the beginning of another major conflagration should they fail.

The jumps in logic are easily overcome by the pacing and the performances. When Bob figures out that the safe house is behind the temple, and has deduced the assassination at the Albert Hall, he wakes Clive from a hypnotic stupor and has him call Jill to head for the Hall. When I first saw the film, I remember being on tenterhooks at the end of the Clive-Jill call, because as it is shot, you’re left wondering if Clive actually got through. It’s a moment that passes quickly enough but serves to underscore and deepen the suspense. Of course, Jill gets the message but it’s a story beat interrupted and thereby lengthened by cutting to Bob on his way to finding and securing Betty.

I need to mention that through it all, everyone has been extremely British throughout. Remove the circumstances and urgency, and there doesn’t seem to be much of a difference between Fred and Alice in Rich and Strange and the Lawrences here in terms of how our principles meet each turn in the script. The humor is bone dry but there is an undercurrent of despair. For Alice and Fred, it’s more about their relationship and their failed dreams; for Bob and Jill, it’s considerably more other-focused. In both cases, though, the couples are (well, in Rich and Strange, perhaps only initially) united by a common goal.

There is no denying that the quality in acting is considerably higher, as well. Banks, Best, and the rest of the ensemble are far more comfortable on camera and with each other and the dialog is delivered with much more naturalism. Part of me does want to relent and say that I do understand where Hitchcock’s desire to remake the film came from, but I still feel it’s far too rich and enjoyable to dismiss as he did.

In any case, Bob falls into the hands of Abbott and his gang while Jill makes it to the Hall where Ropa, the dignitary is attending a concert. We know that he will be shot during the cantata during a crescendo as cymbals clash, the idea being that the tumult will cover the sound of the gunshot. In one of those moments of utter narrative illogic, we see Jill piece together the plot almost as if in a trance and she lets out a blood-curdling shriek just at the moment of the cymbal rising-gun shooting. Ropa is hit but not fatally, but the gang doesn’t know this from the performance they’re listening to on the radio.

Jill carries the film as the central protagonist from here as she tells the police about the plot and where the terrorists are holed up.

About those terrorists/anarchists; Lorre moves from charming to chilling throughout this film in a way not seen on camera before, I think. The cell, particularly his Abbott and his Nurse Agnes and a young girl accompanying them early on in the film and later missing, mirror the Lawrences and by extension, Ramon and the rest of the group provide the threat of disruption and destruction that drive the Lawrences to act more quickly and skilfully than perhaps the British Foreign Service might.

That said, the denouement feels as though it presages similar stand-offs we’d seen in the late 30s crime dramas and beyond. There’s a tense build-up as the London police called in to secure various holds from which to get a bead on the cell. This is also a fascinating moment in shooting the film that has been remarked on, but worth noting for what Hitchcock encountered in the process of making a film. /

The censors objected to the idea that Hitchcock was recreating the Sydney Street shooting of 1914 where the British Army was brought in to subdue Russian anarchists. The censors feared this would remind filmgoers of one of the worst domestic acts of violence and failures of judgment. Hitchcock argued that it was necessary to arm the police (English police don’t carry weapons) and reached a compromise with the censorship board that they would be armed with antique firearms.(1)

In some ways, this actually generates greater suspense, particularly when one policeman is felled after setting up a barricade with a mattress talking about taking a nap himself. He dies as quietly as Louis did at the beginning. Indeed, there’s a gutting casualness to the violence throughout the sequence. The first moment comes when a policeman is gunned down in a longshot; the street scenes draw on a quasi-documentary feel.

The stand-off has sometimes been dinged for going on too long, but I think that misses the point of how surgical Hitchcock is in showing us the increasing tensions between the cell and its members, the growing desperation of Bob as he works to free Betty, the dialog between the neighbors in the area and the police coming to use their flats as stake-outs.

The members of the cell are picked off one by one. It’s critical to note here that the sound design is almost more important than the visuals. Under the constant cacophony of the barrage, you’re not sure who’s going to be next and it seems extremely likely that it could be Bob or Betty struck by a random bullet. Speaking of which, Bob is able to get Betty to the roof where she is pursued by Ramon, the sole survivor.

In a reprise from both the beginning of the film and of her solving the details of the assassination attempt, we see Jill come forward with a rifle and pick off Ramon. Jill wins their second match. There is no recap or extended scene to end on; the family is reunited and that’s where we leave them.

Knowing what Hitchcock had to work on and endure for the previous three years, The Man Who Knew Too Much feels like a catharsis. Dispirited after the debacle of Waltzes from Vienna, here was the U.K.’s first great director at his nadir and very much considering quitting the industry. That said, reteaming with Buchan and galvanized by the prospects offered by working with Gaumont were the twin shots in the arm he needed.

It’s a mistake to consider these films the ones where Alfred Hitchcock became “Hitchcock”. As I hope I’ve made clear, he was in full command of the material by Murder! Even before, for that matter. But it’s with The Man Who Knew Too Much that Hitchcock could pick up where he left off and up the ante.

For one thing, Hitchcock is able to use his almost geometric approach to narrative to full effect. The twinning or doubling has been remarked on already, but also, Hitch’s penchant for subverting roles is on full view for the first time. It is Jill who presents as the sexual alpha, flirting openly with Louis early on and the easy, sophisticated banter between her and Bob feel like a very British approximation of that between Chandler’s Nick and Nora Charles. The difference here is that it is Jill who does the actual dirty work of killing a man, while Bob reads more as their daughter’s caretaker and protector, it is ultimately Jill who has taken on the larger contextual forces of assassination and murder.

Another dimension of the mirroring of Abbott and Agnes and the vanishing/disappeared girl to Bob and Jill and the disappeared Betty, it is telling that Hitchcock draws us up to the line where pair is equally adept at completing a mission - including killing to do so - as the other. It’s worth considering the moral and ethical questions that Hitchcock imposes on his audience here and in similar, later films where the protagonists are forced into actions opposite to who they think they are or even, as in Torn Curtain, where they encounter just how hard it actually is to kill someone. In Hitchcock, even in these earlier films, violence is never seen as anything but quick and dirty. The ramifications are often tacitly assumed and I believe deeply felt by the protagonists when they are forced into the theater of conflict. Jill is not thrilled that she had just killed a man, but obviously, she was left no choice.

It is telling, too, that despite the censors feeling that the shoot-out had the potential to paint the police in a negative light, it is the police (well, one policeman) who refuses to take the shot for fear of shooting Betty. Again, as a critical subversion, it is Jill who takes the reins here.

Charles Barr emphasizes a deeper psychosexual tension to the banter than I feel like the dialog warrants. I don’t disagree that it’s there, given Jill’s almost masculine dominance, but I think the character Bob Lawrence becomes all the more fascinating as an object for analysis. It is he who spends the most time with their daughter, who pursues the terrorists, who deals directly with Abbott, and who puts himself in danger’s way repeatedly to find and protect her. True, there’s little of what we can normally code as “masculine posturing”, but that points back to the utter Britishness of it all.

I don’t know if Hitchcock was taking a potshot at the critique of the effeminate Englishman or if this was his own critique of British masculinity, but of all the early male protagonists, Leslie Banks may be the most soft of them all. I rather suspect it may be by design, though, particularly in his scenes with Lorre.

It’s too commonplace and almost silly to go on about Lorre as an actor. However, it’s a remarkable turn for a guy who spoke little English at the time, learned most of his lines phonetically and yet, was palpably present for his scene partners.

It also helps that Lorre’s appearance is physically soft to match off against Banks’ more emotionally sympathetic nature. Then, there’s the flip side to that; Lorre’s Abbott is a stone killer. It also helps that Lorre has, beginning in this film, already formed his approach to similar characters, purring the dialog like a cat savoring the remains of a mouse she’s murdered by playing with. The following exchange, even in print form, should given an idea.

Abbott to Lawrence, “You know, to a man with a heart as soft as mine, there’s nothing sweeter than a touching scene.” To which Lawrence responds, “such as?”

“Such as a child saying goodbye to his child. Yeah, goodbye for the last time. What could be more touching than that?”

There’s also (relatively) easy back and forths between Banks and Lorre while Bob is held captive. Again, Lorre anchors his performance with a novel wit. I won’t say that he walks off with the movie in every scene he’s in - he’s too generous an actor to do that - but it wouldn’t have been impossible.

There is also a structural-thematic rhythm in his films that Hitchcock solidifies with this film; the back and forth between chaos and order and though not in this case, very often in later films, the interplay of both. Structurally, the tension between the two is what builds and sustains genuine suspense but/and it may also be why, very often in Hitchcock’s cinema, we aren’t left with a catharsis or exultant at an outcome, but mostly, relieved.

I’m not trying to make a case for Hitchcock as a political filmmaker, but I will return to how he uses the power of the state as both a context and an often antagonistic force. This folds neatly in with, among other things, the psychological construction of his characters as well as the plots they are part of.

Hitchcock is also, and no one will convince me otherwise, not a promoter of freewill. Yes, his heroes and heroines often succeed against formidable odds, but at the end of the day, it’s because they had no choice but to succeed. Very often, Hitchcock’s Catholicism seems to underpin his films, particularly in a kind Pauline way; most assuredly not Augustinian.

For example, neither of the Lawrences are motivated by any kind of altruism to assist the State (or the world, for that matter); their motivation is to save their daughter and preserve their family. A charitable reading would be preserving the sanctity of the family trumps acting for the security of the nation, perhaps. However, it is their motivation to find and save Betty that results in justice by the state being served. In this and in other films, it could not be otherwise.

There is a pronounced fatalism in Hitchcock’s work and I am hard-pressed to find an alternative reading across his body of work to that conclusion.

Consequently, is there then redemption in Hitchcock’s movies? Some would ask why there should be; the bad guys get their comeuppance, order is restored. However, this is a facile and simplistic reading of texts that have proven to be anything but.

By the end of almost every Hitchcock film, even including his non-thrillers, there is the sense that disorder and entropy will intrude again on the characters left at the end of each story. Fred and Alice, no less than Bob and Jill, are going to encounter additional trials later; while it is unlikely that those trials will be as severe as almost drowning at sea or watching your daughter die at the hands of a terrorist, implicit in Hitchcock’s telling is that there is a sense of trauma that will continue on after “The End” has put a bow on it all.

This also calls into question whether there is genuine innocence or innocents in Hitchcock’s work. Even children are seen to be agents of disruption and disorder and therefore ripe for reprisal, however harsh and/or misguided. The world is a fallen place and I don’t wonder that Hitchcock’s Jesuit education didn’t inform his approach to storytelling.

I’ll probably say it again over the course of the remaining films, but I don’t believe Hitchcock believed in happy endings. This is fitting because, as has been amply demonstrated by his own works in addition to decades of analysis by others far more adept than myself, he was a complicated human being whose work reveals greater complexity because of that complicated nature.

In the next film, The 39 Steps, we’ll encounter his first use of a blonde movie star for what will become an archetype in his work. Jill, here in The Man Who Knew Too Much, is not that (though Betty is and Nova Pilbeam will show up in a quite different capacity in Young and Innocent a few years later.) Hitchcock’s complexity extends to his fetishization/abuse of his female leads and we’ll come to see that as more pronounced in his American films, though its genesis is firmly planted on U.K. soil.

Appendix: Source for the material and observations about cinematography

The source for the film was originally to be a story based on the Bulldog Drummond character. Frankly, I would have been overjoyed to see what Hitchcock would do with a character like that. The Bulldog Drummond series was adapted in a string of films that are great fun (portrayed by luminaries like Ralph Richardson, Ray Milland, and Ronald Colman, but mostly by John Howard.) They're intelligently done but in Hitchcock's hands, I would assume there would be drastic changes to the character, and likely, Hitchcock would have been frustrated by the constraints of adapting a pop culture figure that well known.

According to Barr, the Drummond connection "remains unofficial", although there seems to have been discussions between Gerald du Maurier who made the first adaptation of Drummond for the stage and that, while at BIP, Bennett had worked with Hitch on a story. This didn't get developed then but it seems Hitchcock buought the rights to the story and resold them to Michael Balcon when Bennett and Hitchcock went to Gaumont.

This is the first of five consecutive collaborations with Bennett, about whom more can be found in the Collaborators page.

Photography is credited to Curt Courant who had worked with Lang and would also work uncredited on Chaplin's Monsieur Verdoux. It's again difficult to say exactly where a DP comes in. Bernard Knowles and J.J. Cox who would take over the remainder of the thirties films were certainly more than competent cinematographers, but ultimately, it's Hitchcock's own visual sensibility that calls the shots. Courant's blocking and set-ups - dictated by Hitchcock or not - drill down into intimate levels and zoom out to - as mentioned above - an almost documentary degree of objectivity.

The use of focus to capture, say, Jill's point of view, coming out of the faint after receiving news of Betty's abduction can be contrasted with the tight shot on her when she's in the Hall just prior to the assassination attempt and her abstracted expression framed during that sequence. The fight scene in the temple is shot in high contrast - sharp angles, sharp highlights, and deep darks - but you know where everyone is in space and point of view shifts just as angularly. It is quite simply, a thrilling flick to watch.

Note

Hitchcock, pp. 192-201. Also in Truffaut, pp. 89-90

Bibliography

Barr, Charles. English Hitchcock. Cameron and Hollis. Dumfrieshire, Scotland. 1999.

Hitchcock, Alfred. “The Censor and Sydney Street - An Interview with Leslie Perkoff” and “The Censor Wouldn’t Pass It - An Interview with J. Danvers Williams” in Hitchcock on Hitchcock - Selected Writings and Interviews. University of California Press. Berkeley. 1997.

Truffaut, François with Scott, Helen G. Hitchcock. Simon and Schuster Touchstone. New York. 1985.

Comments

Post a Comment