Anna May Wong - Before the Toll: Uncredited and Early Roles, Part 1

|

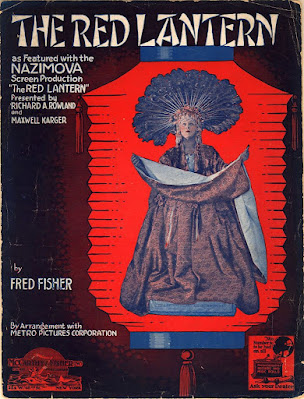

Context and the mileux of The Red Lantern

At fourteen, the young Anna May Wong fully besotted by motion pictures, was picked as one of 300 Chinese and Chinese Americans for a crowd scene in The Red Lantern, starring Alla Nazimova, at the time the most celebrated actress in cinema and renowned for her theater work.

The film centers around Nazimova in yellowface (and this term will show up repeated throughout this series) in a dual role as Mahlee, a Eurasian woman and Blanche Sackville, her half-sister (who is fully caucasian.) The backdrop of the film is the Boxer Rebellion of 1901 and while I will be reviewing it elsewhere, due to this series being about Anna May Wong, I'm giving it a more than passing mention because of its and Alla Nazimova's significance in AMW's life.

It is difficult to overstate how much movies meant to Anna May Wong as an adolescent, how important Alla Nazimova was in cinema at the time, and how pervasive women and the power they wielded in the industry were.

Additionally, it's worth noting that the film was produced during the end of the World War One and during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. To hammer a nail that doesn't need it, a lot was happening in the world. The Nineteenth Amendment would be signed into law in the year following The Red Lantern's release, but suffrage would not ensure freedom from racial prejudice nor would the Chinese Exclusion Act be repealed for another two decades.

Anna May Wong was entering a film at a time when a substantial number of women were not only actors, but studio heads, producers, directors, editors, and more. Film scholar Anthony Slide noted that there was "more than 30 women directors prior to 1920, more than any other period in history."(1) This is to say nothing of other behind the camera workers.(2) It may also be salient to bear in mind that women provided the majority of audiences. (3)

If the motion picture industry held some promise, some kind of open frontier for the pursuit of dreams, society at large may not have seemed quite so exciting. To be sure, the country overall was doing well enough. The United States was decade away from the 1929 Crash of Wall Street that would signal the arrival of the Great Depression.

On the surface, the U.S. economy was growing, and in general the standard of living was improving. This would belie the counter-narrative of how immigrants, the poor and other disenfranchised populations were treated. Yunte Huang points out the immense racism that Chinese Americans like Sam Wong and his family faced in Los Angeles.(4) If we look abroad, outside the state of California, there was similar marginalization of Chinese people across the country. (5)

With the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of1882, xenophobia and racism found its first legal support. The Jim Crow Era that would afflict and continue the oppression of Black people after Restoration found unfortunate echoes in legislation restricting the rights of other ethnic minorities who had, indeed, lived in the country for generations.

By the time Anna May was born, the Progressive Era had been gaining traction since the late 1890s. That it was progressive in terms of broad social changes is open for debate. While some major advances were made to improve the overall quality of life, it doesn't take much investigation to see that improvement was more selective than many would like to admit.

What we encounter here is, of course, the systemic racism that whether we admit or not, is part of the bedrock of the republic. As we'll find over the course of Anna May Wong's career, this is an idee fixe across her lifetime and arguably, into the present day. (6)

We know that by the time Anna May was in high school, her father had moved the family to a particularly vital and diverse part of Los Angeles. There was a melange of people, cultures and languages.

We have a pretty good idea of the young Anna May as a fun-loving, rebellious young woman, enamored of the cinema and as far as these characteristics go, she wasn't unusual. That said, she most certainly was; of her contemporaries, her love of the movies found expression in moving from background actor/extra to walk-ons to credited roles to, well, becoming Anna May Wong.

One of the reasons why Anna May Wong is as celebrated as she is is simple. She beat the odds. She beat the odds out of that kind of seeming destiny that all transformative people seem to have to follow. We can fit together the various turning points in her life and string them up like a garland and say, so full of ourselves, "well, of course, this is how it had to be!" But in light of the milieux and singular milieu into which she was born, nope. It was not a given that she wouldn't be ignored and discarded before her time.

We can say how fortuitous it was that Alla Nazimova took to her, or that she caught the eye of Marshall Neilan or Chaney or whomever, but fortune only goes so far. At fourteen, an extra in a vehicle for arguably the most famous and powerful woman in films at the time, Anna May Wong seized the moment and capitalized on this toehold in what was no longer a fledgling industry.

It is of dubious value to try to gauge in retrospect what elements led an artist to her successes. It's easier to identify and chart the roadblocks and obstacles. These would remain constant until her death; we tend to be struck by her successes because, frankly, she was the only Chinese American movie star. Even in her declining years, she was still well-regarded professionally and her cachet certainly extended far enough that she became the first woman, let alone first Asian American woman to produce her own TV show. We'll get to these points over time, but for now, I want to look, however briefly, at her early roles.

They aren't huge. But she made an impression and one can only assume that she looked around and realized that she was the only person who looked like her, who had sufficient motivation, who could forge ahead.

Her turns in the surviving films don't take up a massive amount of screen time, but they set a tone for other roles to come. Obviously, we don't even know who she is in The Red Lantern. She wasn't sure where she appeared on screen, either. It doesn't matter; for the moment, what happened outside the film is what's important.

Next, we'll take a look at her extant early roles before her breakthrough in The Toll of Sea. As her profile rises, her life grows more complex, due in no small part to her own complexity as a person, but it's a rich life with depths that only grow over time.

Notes

1. Quoted in Brussel, 2017.

2. "Women screenwriters — the most well-respected and well-paid being Frances Marion, Jeanie Macpherson, Anita Loos, June Mathis, and Bess Meredyth — wrote half of the silent films copyrighted between 1915 and 1925, according to Beauchamp’s Without Lying Down. A woman, Lois Weber, was the highest-paid director in town. It’s no surprise that one commentator referred to this landscape as a “manless Eden.” " See Nicolaou, 2018.

3. Definitive metrics are difficult to find. Genuine record-keeping didn't begin until 1930, but a rough estimate seems to be that by the end of the 1920s, audience attendance was somewhere around 80 million people.

4. Huang, pp.

5. Huang points to the Los Angeles Massacre of 1871; see also, the 1885 Massacre at Rock Creek, Colorado and the Deep Creek Massacre in Oregon in 1887.

6. See Connelly for an astute article on the legacy of the Chinese Exclusion Act and also on the Library of Congress website, "Cities During the Progressive Era."

Bibliography

Brussel, Angela. How Women Dominated the Silent Film Industry. ARTPublika. April 1, 2017. https://www.artpublikamag.com/post/how-women-dominated-the-silent-film-industry.

Gaines, Jane; Radha Vatsal. "How Women Worked in the US Silent Film Industry." In Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2011. https://wfpp.columbia.edu/essay/how-women-worked-in-the-us-silent-film-industry/.

Nicolaou, Elena, The Silent Era was a "Manless Eden" for Women in Film. Refinery29. 25 April 2018. https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/2018/04/197127/women-silent-era-hollywood-prominent-directors-writers.

Pierce, David. The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929. Library of Congress publication no 158. Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. September 2013. https://www.clir.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/pub158.pdf.

Comments

Post a Comment