'tis the Season: Zombies!!! White Zombie (1932)/I Walked with a Zombie (1943)

Before intelligent zombies, before the zombie genre-as-thematically-rich, before cannibalistic zombies even, the zombie was a useful and provocative tool for the bad guy in its earliest iterations. This is not to say that the early films weren't thematically rich, but at a remove of ninety years, the themes are imposed by advances in civil rights and how we view the effects of colonialism and cultural appropriation. I'll add, too, that as with so many films we find challenging from earlier eras, this doesn't necessarily stop them from being entertaining.

Both of the films here use the zombie in its form as a kind of golem; resurrected dead to be employed for labor or executing someone else's will by the use of Voudou/voodoo rituals or ancillary animistic magic.

A cursory glance into the word's etymology is enlightening:

"also zombi, jumbie, 1788, possibly representing two separate words, one relating to the dead and the other to authority figures, but if so historically these were not kept distinct in English-speaking usage. The oldest attested sense in English is "'spirits of dead wicked men [...] that torment the living.'" The sense of "reanimated corpse" is by 1929 (Seabrook). The word usually is said to be of West African origin (compare Kikongo zumbi "fetish" and djumbi "ghost). A sense of "slow-witted person" is recorded from 1936.

It also is attested from 1819 as a title for a chief, in an Afro-Brazilian context. This is said to be directly from the Angolan (Kimbundu) nzambi, "deity." The meaning "witch" is attested by 1910, that of "deity" is by 1921. Grand Zombi as the name of a deity in Voodoo practices is in English by 1904. Zombi was also used as a name for pets in 19c."

From Etymonline, "Zombie"

Thus, we can infer another instance where a term that had a more nuanced meaning entered common usage via colonist attitudes to be related to something exclusively dark and/or malevolent.

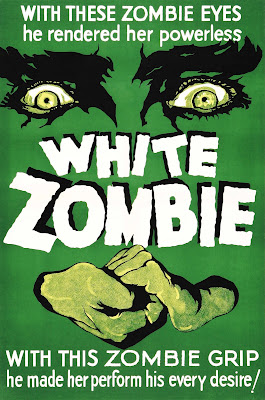

As we'll see in various other examples from the 1930s and 1940s, "zombie" - likely unintentionally but nevertheless reflective of the period - is a codeword for Black person. Consequently, the very title "White Zombie" speaks to the exceptionalism of the victim and why she needs to be saved exclusively, over and against others.

Admittedly, this is complicated because Madeleine Parker (Frances Dee) isn't quite as dead as others on the island. My supposition is that she was put into an arrested state of suspended animation as opposed to full on decease. However, having said that, Bela Lugosi's Ledendre avers that were he to restore his former enemies to their pre-zombie state, they would tear him apart. So we're left with the idea that not all zombies in White Zombie are quite totally deceased, dead, ex-people.

White Zombie is referred to as the first proper zombie movie. It could be argued that Abel Gance's J'accuse! from 1919 has elements of zombiefication, but it's too much of a stretch to validify. With the movie at hand, we are in Zombieland proper.

It's a nifty little film and Victor Halperin approaches the material with a studied eye toward composition and well-played editing. There's a diagonal split-screen moment when Madeleine is rising from her stupor far away from her beloved Neil. She's in the upper half, he's in the lower and it's far more effective than it might otherwise be owing to the set-ups in their respective framing.

In fact, there are a number of shots that are quite eye-catching; some remarkable matte work and compositing for the period. Halperin had a steady hand for melodrama as well as the supernatural, much of it from his work on stage prior to entering the film industry in the mid-1920s. Consequently, that might be where the movie falls short, particularly to modern eyes and ears; it's pretty, well, stagey. Additionally, the acting styles that predominate are very much of the previous era; Madge Bellamy, who plays Madeleine, began her career in 1920 and never quite transitioned to a more naturalistic approach to film acting. Robert Frazer (Charles Beaumont) is less stagebound but still employed a lot of the physicality that we associate with the pre-sound era. This is fitting, though, for the guy who was the first to play Robinhood on screen. Frazer had a fairly long career despite dying at 53.

Madeleine's fiancee (at the beginning of the film, husband in the course for the movie) Neil is played by John Harron whose career was pretty much the norm for many who came out of the twenties that didn't make a successful transition to sound. Like Frazer and for that matter, Lugosi, Harron found himself in second-rate pictures before his untimely death at 36.

Ah, Lugosi. Bela, Bela, Bela. One of the more tragic figures in cinema and yet few have left as indelible a mark on the horror genre; but I would also add that he opened doors for a style of acting that is almost unique to him. He could ham it up unrepentantly but he was equally capable of bringing humor and wit to a role where he could. White Zombie is a case where we see more of what Lugosi was capable of quickly relegated to going back to being the suave Eastern European bad guy.

There are a couple of scenes where Lugosi towers over his scene partner (let's not forget that he was six foot one) and is both menacing and actually very charming. I really do feel a case could be made that with more enlightened casting directors and studios willing to take a chance on actors like Lugosi, he might have made a seriously good leading man on the order of Charles Boyer. However, for a variety of reasons, this was not to be and we see a torture addict of an actor's reputation spiral down into the hands of Ed Wood in his sunset years.

Altogether, White Zombie succeeds on its story structure and atmosphere than on writing and the performances. This isn't unusual; very often, it's the case for many of the early 1930s horror films, but it does set itself apart with Lugosi's performance and some beautifully composed shots.

Of course, it's a preposterous story; a young couple have been invited to an almost total stranger's plantation on Haiti. Charles Beaumont has fallen for Madeleine and knows that he doesn't have a chance, so he rigs the game by enlisting Lugosi's Legendre in drugging and zombiefying her. She "dies" at what is supposed to be the celebratory dinner at Beuamont's and is interred in a crypt from which her body is later removed (by Legendre's zombie slaves) and soon enough, Beaumont realizes how empty the relationship is when the object of his desire can't respond to him in any meaningful way.

Neil goes on a bender and is eventually later convinced that Madeleine may still be alive and is aided by the kind Dr. Bruner to find her and free her from Legendre's power. Along the way, Beaumont is killed, of course, and Legendre is thwarted by Neil's love for Madeleine and once the spell is broken, is chased to his death by his enemies-turned-zombies cohort. They don't tear him apart - and their not really freed from their enslavement as fully as Madeleine - but they do kill him (and then follow suit by one by one dropping off the high precipice where his castle is, onto the rocks below). True love conquers all.

Ten years later, fresh from their collaboration on Cat People, Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur turn their psychological approach to horror onto the zombie genre. It, too, is a tour de force of atmosphere, but more nuanced in its approach to character and thematic structures. Frances Dee plays young Canadian nurse Betsy who lands a job as caretaker for Jessica, the wife of Paul Holland, a plantation owner. She is cataleptic and unresponsive to any but the simplest of commands.

Jessica's doctor, Dr. Maxwell explains that Jessica was consumed by a tropical fever that "burned out" her spine and left her in this state. Complicating the situation is Wesley Rand, Paul's half-brother, who needles/harasses Paul over Jessica's state. Paul himself had warned Betsy that there is no beauty on the island and is very often downright nihilistic. Wesley is a drunk. Additionally, it becomes obvious that Betsy has fallen for Paul, but wants to help bring Jessica back nonetheless. She's got a good heart, that Betsy. When an insulin shock treatment fails, Betsy wonders if voodoo might help; she's befriended the servants at the estate and has come to learn a bit about the beliefs of resuscitating the dead held by the islanders.

Naturally, attempts are made to dissuade her, particularly by Wesley and Paul's widowed missionary mother. Of course, Betsy is taken aback when she attends a ritual in the village to cure people of disease and hopefully, including Jessica, and Mrs. Rand appears. She uses her cachet with the natives to guide them away from their "superstitions" and while there is little discussion of her religious leaning in the film beyond mentioning she was missionary (or just a missionary's wife), but concentrates on how she has worked with the hougan (Vodou priest) to be perceived as one through whom the spirits speak so she and Dr. Maxwell can tend to their medical needs.

A couple of elements capture the eye and mind around this part of the story. One is how seemingly of an almost environmental piece the discussion of an alternative therapy for Jessica Vodou might provide; another is how melancholy as opposed to dreadful the atmosphere in the film is, and even how Carrefour, the zombie who guards the crossroads to the houmfort (the Vodou temple) is less an object of horror or threat than, as Peter Dendle says in The Zombie Movie Encyclopedia, "a natural part of the cane fields and sandy shore, themselves dark and mysterious-he is, as it were, an embodiment of the will of the natives and of the land itself, a will expressing disapproval of the moral trespasses of the decadent colonialists”.

I want to pause here to recognize that while Lewton and Tourneur are not taking a strong anti-colonialist polemical stance, they do bring up the racist/slave past of the island Saint Sebastian. Indeed, an early discussion between Betsy and a coachman centers on the tales of the shackled slaves and how a remnant of the slave ship owned by the Hollands' ancestors remains at Fort Holland, a figurehead of the Saint himself. The film doesn't center on the slavery theme directly, but it does I think, take some pains to establish that the lack of agency felt by a zombie is very much a metaphor for the enslaved.

Of course, like White Zombie, the object to be rescued is once again a white woman. This brings us to another theme pervasive in these early zombie films (and certainly not limited to them, but they are the surest example of sexism yet in a genre). the appropriation/enslavement of women at the center of the narratives; exclusively white women. Additionally, while this is not the case with I Walked with a Zombie, it is much more so the case with White Zombie, the use of the woman's body is transparently erotic, if coded under the rubric "romantic". In the Lewton/Tourneur work, Jessica is a plot point more than a person who once possessed agency and yet, even so, she is regarded by all who discuss her tragically.

I should mention that we learn of the cause of tension between Paul and Wesley stems from Paul learning that Jessica was going to run off with Wesley before her illness. Consequently, when Betsy shows her concern for Paul and he tells her he no longer loves Jessica and that she should leave Saint Sebastian, none of this registers as surprising. Nor would it be if anyone's read Jane Eyre, upon which the film is based.

In any case, the night before Betsy is ready to depart, Wesley sees Jessica leave the compound. This had happened before when the houngan had issued orders that Jessica be brought back to finish her treatment. Wesley and Betsy were able to stop her the first time. This time, Wesley abets her exit; he grabs an arrow from the figurehead's chest and follows her. She is being drawn along by sympathetic magic at the houmfort where the houngan's assistant is pulling an effigy of Jessica toward him. At a certain juncture in the ritual, he plunges a knife into the effigy and near the ocean, Wesley plunges the arrow into Jessica. He sends her body into the waves and follows suit to drown himself. Carrefour is sent to retrieve Jessica but halts at the beach as we look out over the ocean.

Subsequently, we see Betsy and Paul consoling one another and the movie ends on a less melancholy note, though not exactly a happy one. As with their other collaborations, there is a sense of entropy, tragedy, and sadness.

This latter point is key to the importance of Lewton and Tourneur's works. They established an approach to a genre that before them, had scarcely examined the possibility of incorporating broader and deeper themes, let alone social commentary, and even doing away with the idea of a singular creature or monster as the focal point of a "horror" movie.

In this regard, their works presaged the more thoughtful approaches to the genre of which we see more and more in contemporary times from the likes of George Romero and Nicholas Roeg in the sixties and seventies to Jordan Peele and Bong Joon-ho today.

As for the cinematic quality of I Walked with a Zombie, it's difficult to overpraise it for its narrative economy, the performances (both Frances Dee as Betsy and Tom Conway as Paul work wonders and are excellent scene partners; this extends down to seasoned pros like Edith Barrett as Mrs. Rand and James Ellison as Wesley), and the rich cinematography from J. Roy Hunt whose career spanned forty years beginning in 1914. Hunt's work was mostly in westerns and action flicks but here it's subdued and employs a shrewd use of depth of focus and framing that accentuates the general sense of decay of Fort Holland and the uneasy stillness of the cane fields and the ocean.

It's the ambient aspects of the film that serve the psychological underpinnings of the narrative. In addition to the racial/social and gender-related narrative tensions, there is a sense of turmoil and decline that is mirrored in the physical trappings of the drama. Tourneur's work is often referred to as B-movies, but I detest the idea that B-movies can't be complete works of genius. They're just genius on a budget.

There are a couple more early zombie movies I want to look at before moving into more recent periods (and by more recent, I mean the sixties; I'm so overdue for rewatching Night of the Living Dead that I think I decided to do this series for Halloween this year just so I'd have an excuse for that rewatch!)

Bibliography/Additional reading

Dendle, Peter. The Zombie Movie Encyclopedia. McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers. Jefferson, North Carolina. 2001.

Jancovich, Mark. Relocating Lewton: Cultural Distinctions, Critical Reception, and the Val Lewton Horror Films. Journal of Film and Video, Vol. 64, No. 3 (Fall 2012), pp. 21-37. University of Illinois Press on behalf of the University Film & Video Association. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/jfilmvideo.64.3.0021

Comments

Post a Comment