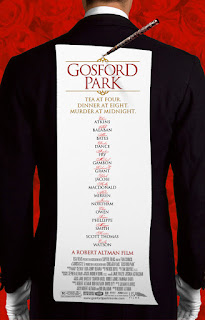

Last Watch of 2024 - a return to Gosford Park (2001)

I finished last year strong with Poor Things and there is nothing of that ilk out right now. I am going to see Babydoll later as the first movie of 2025, but I knew Sis wanted to watch a flick and we had been discussing Gosford for years.

It’s not just that it’s a stacked cast with some of the greatest actors of several generations or that Fellowes delivered the sharpest script of his career; it’s that it’s one of those premier examples of how film is a collaborative medium and that Bob Altman knew that better than many, if not most.

When he fired on all cylinders, Altman turned out at least a dozen genuinely great films. When he wasn’t quite as inspired, he had control of his craft enough that even the most workmanlike movie was still pretty entertaining. And like everyone, he had his off cays and more than a couple of his sub-par works suck.

But not here.

Altman always had an eye on class and the codification of and limitations to relationships that class divides create. “Class” here could mean the stratifications in the music industry in Nashville, more obvious references in A Wedding, and via illicit relations in Fool for Love and others. Hell, Brewster McCloud might even hit the button.

Gosford Park was tailor-made for Altman. It shows him paying homage to Jean Renoir’s masterwork Le règle du jou/The Rules of the Game and classic whodunnits and drawing room intrigues.

He takes a shrewd look at the demise of the British Empire, of the waning days of peerage, and the baser intrigues alluded to, typically motivated by money; especially, money for maintaining the appearance of one’s place in “polite society.” Percolating underneath it all, is the roiling resentment of an underclass whose lives their societal superiors depend on and how they navigate that relationship. Unlike Fellowes’ later work, the series Downton Abbey, Gosford hews much closer to the actuality of how the classes co-existed under one roof. You feel the end days of the last vestige of feudalism decaying before your eyes here, and there is no buddy-buddy support by the higher for the lower that we encounter in the Fellowes’ series.

Don’t get me wrong; I love Downton! I do, but it’s a kind of weird wish-fulfillment for an era built off the backs of oppression that inspired Marx and Engels to write A Communist Manifesto and for Marx to deliver Das Kapital to the world.

In a film jam-packed with outstanding performances, there is no “best”. Quite frequently, there are small turns and moments that are as expertly acted as the more main pieces, but again, this is a testament to a director who had faith in his cast and loved actors. He knew hoe to give people space to perform.

You could also frame a kind of dialectic approach here, matching off the “upstairs” players to the “downstairs” and running parallel. The mysteries extend beyond the murder of a patriarch and into the nature of identity and how exploitation and using people as vessels for mere casual pleasure results in extensive generational trauma and destroys the fabric of families. The patriarch meeting his end is perhaps a symbol of the patriarchy coming to its end.

All of this doesn’t get at the dark fun to be had here. It doesn’t and can’t get at the wit of Fellowes’ script or convey Maggie Smith’s deadpan delivery or Ryan Phillippe’s idiotic valet-not-a-valet and his comeuppance, or perhaps mostly, Stephen Fry’s turn as the detective called in to investigate.

And there’s heart throughout. Relationships come into focus that run their course and leave a lasting longing of aching proportions. I can’t and won’t say anything specifically, but Clive Owen's valet has a secret that ties explodes what’s at the root of the rot of the upper classes here. Kelly MacDonald’s maid is a supportive friend to Emily Watson who’s outburst at one point, will send her back into the world, unemployed and homeless. MacDonald is alto the observant who solves the mystery and this, in turn, delivers us to a wrenching scene between Helen Mirren and Eileen Atkins that wrecked me when I first saw the film and still gets me on repeated viewing.

Michael Gambon, Kristin Scott Thomas, Smith, and others render the social elite as humans trapped in their own stratification, clueless to the historical forces that are harbingers of the twilight of their era. To be sure, they mention World War One and the declining fortunes of the British Empire in 1932, but for the most part, don’t seem to realize what this means for them. Perhaps Krisitn Scott Thomas’s character at the end has a glimpse of what’s to come; she’s spent from the drama of her marriage, the murder, and all of it. She seems too tired to care about what’s next or perhaps it’s just knowing that she has the money to live off of that downsizing won’t be that big a deal and she’ll likely carry on.

Then there’s Balaban himself as a Hollywood producer, whose next film will be Charlie Chan in London (1934; it’s a real movie) and Jeremy Northam as Ivor Novello, the great Welsh thespian/singer and composer. Novello is invited to the gathering for a weekend to the Trentham mansion and serves as our (and Balaban’s Weissman’s) guide to the goings-on among the weatlthy and their servants. Weissman is more the audience surrogate, but there are shifts in POVs throughout from one character to the next as Altman employs his fluid camera work throughout. The camera is never still, even in moments when you might think there’s s stillness, there’s often a subtle movement that glides into he next shot; Andrew Dunn’s work here is exemplary and unfussy; it’s at complete service to the story/stories.

When the film ends, the immediate sense is of a perfect meal and one fo the most satisfying cinematic experiences; but then, you start to reflect a little bit. While one form of class divide met its end, for the most part, it’s not over by a damn sight. As with M*A*S*H, Altman wasn’t just looking backward; he was looking at recent history. As that film was more about Vietnam, so Gosford Park was a look at how power and exploitation remains pervasive and is used to maintain a “social order” for the privileged few, until someone steps up to end it. For sure, Altman is not a didactic director (though he could be), but in this instance, the resonance of his observations in 2001 ring more loudly this many years later.

Comments

Post a Comment