To the White Lodge: David Lynch (1946 - 2025)

|

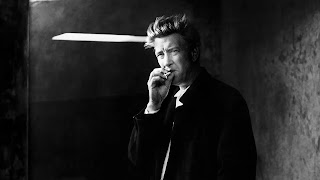

| David Lynch by Martin Schoeller/Art + Commerce |

You reach a certain time of life and you recognize that we don’t go on forever. People we love and admire don’t live forever. That said, I hoped I’d never have to write the words “David Lynch has died” because, as with David Bowie, it just doesn’t seem possible that they could die. However, that kind of sentiment - if I genuinely believed it - would show a profound lack of understanding of the artists and their work.

Both were clear-eyed visionaries who saw through the genteel fabric of lies of the constructed realities most people inhabit. Lynch, in particular, saw and felt the underbelly of the American Experience with its Howdy-Doody surfaces covering up a roiling morass of darkness. However, I don’t think Lynch necessarily saw evil as personal; I think he grasped that, if anything, the darker forces the we try to tamp down beneath the surface instead of working them out, are as impersonal as the thunder or lightning on a pitch-black night.

When Jeffrey and Sandy are sitting in the car in Blue Velvet, in one of those fever pitch moments that happens in every Lynch film, Jeffrey tearfully cries how is it possible that a person like Frank Booth exists. Frank Booth is a fact. A hard, scary fact, but at one point in the film, when Frank turns to Jeffrey and says “You’re like me”, we enter the world of doubling, of twinning that played a central part in Lunch’s cosmos. You could be sure that where there’s one, there’s two; and the other might well be the opposite of the first, but inseparable from it.

I saw Eraserhead when it came out and as a punk-ass bitch kid, was reluctant to do so, because I’d seen the surrealist masterworks of Buñuel. I had seen Jodorowsky and lots of “weird shit.” This was different. Eraserhead was replete with loss and tenderness, with apprehension and uncertainty, but it was unlike anything you could point to in contemporary cinema at the time. I was nineteen and saw it twice in the theater. I wasn’t trying to unearth its secrets or decode it; it spoke more directly to a part of me that I knew was there and for which I had no name.

It wasn’t long afterward that I saw a number of Lynch’s short works, including The Alphabet and The Grandmother and decided then and there that the rest of the world can have the Star Wars guy; this is film. By this point, it was more or less common knowledge that Lynch was a painter, that he drew most of his inspiration from painting and didn’t consider himself a film buff. Still, his command of the medium and narrative prowess would be masterful with his next feature, The Elephant Man.

Here is Lynch the humanist, with all the empathy and compassion that entails and framed in a film no less glorious to look at than his first full length work. It was also the first in which he works with actors who could be the midwives of his characters; later would come the shamans. But for now, John Hurt as Merrick, Anthony Hopkins as his self-questioning doctor (was he exploiting Merrick or did he try to be a genuine friend? “Am I a good man? Or a bad man?”, Treves asks his wife. And later, John Merrick himself in talking to Mrs. Trevis says in passing about how he’d like to meet his mother to show her where he was, he notes “I’ve tried to be good.” And here is the moral underpinning to many or most of Lynch’s characters; they simply want to be good, however complicated that desire might be.

His next feature was Dune, about which I’ve not much to say. It fascinated me at the time, still rather does. And I’m still unsure that I’d call it a bad film. There are signature Lynch moments and visual cues that let us know who’s at the wheel but it’s a compromised vision and a lesson Lynch would learn from.

And then comes Blue Velvet, where Douglas Sick meets Sam Fuller with a dash of Grand Guignol, if not giallo. Jeffrey Beaumont is innocence corrupted as is Dorothy Davenport, and Sandy Williams. Dorothy, of course, was rotted earliest, but it’s only a bit later that Jeffrey is taken into darkness. As for Sandy, Lynch keeps her as pure as possible, but in many ways, she is as doomed as any who have come into contact with Frank Booth.

In lesser hands, Dennis Hopper’s Frank would have sucked all the air out the room in terms of acting; but Kyle MacLachlan, Isabella Rossellini, and Laura Dern are more than equal to the task. They have to be. Frank’s psychopath is pure id; his darkness awakens the darkness already there in everyone. Yes, he’s evil and best of all, strange. Dean Stockwell’s Ben (“one suave fuck”) might meet Frank on equal ground, though. In any event, Blue Velvet rips the bandaid off a nation’s scab of moral superiority on the face and said rot and corruption underneath.

Lynch met acting perfection with the recently sober Hopper. Hopper understood Frank so much that he told Lynch, “I am Frank Booth.” Full disclosure; he stayed at a friend’s place in Houston in the early 80s, before he got sober. He was Frank Booth. Anyway, Hopper’s performance is one for the ages, to be sure, but his take on Frank is telling and dovetails with Lynch’s innate humanism. Hopper felt that Frank was motivated by love for Dorothy. A love so strong, so twisted, but strong and twisted because it was so intense. Of course, Hopper wasn’t an idiot; Frank Booth is not a good guy. He’s not going to question himself, but he’s going to consume everything in his path and destroy it.

Of course, he doesn’t. He dies; Jeffrey blows his brains out as Frank is about to enter the closet where Jeffrey is hiding and it’s in this movie where we encounter those hidden spaces that are liminal portals between worlds, where we contact forces that mold the people around us and the people we are, We are the robin at the film’s end about to finish off the beetle held in its been, but we are very much the “good people” (Sandy, Jeffrey, and Mrs. Williams) smiling and laughing at the beetle’s struggle from the kitchen window.

Blue Velvet is the key to Lynch’s later work. The DNA for Twin Peaks is here, for Wild at Heart, Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive, and Inland Empire. It is the ur-text from which you can extrapolate themes and characters. Lumberton is Twin Peaks. It exists at a crossroads between the seen and unseen worlds as surely as the other.

If Blue Velvet is less occultist in its narrative, it is no less incantatory. There is a stunning power to the film that seems to call into beings emotions and feelings for which there are no names and a kind of power issue from the unconscious that resonates deeply with in the viewer. This is uncomfortable, perhaps, for many or for most; but it becomes a kind of safe space for the rest of us who feel there is something out of whack with the world, in the world.

Wild at Heart was almost a sweet little road trip of a movie mashed up with a Wizard of Oz from Hell narrative. Dern shows up again as Lulu and Nic Cage is pefect as Sailor. A perfect Lynch actor; so perfect, it’s astonishing that they didn’t work together again. Diane Ladd is on hand as the disturbing mother and archetype and Willem Dafoe proves himself a worthy addition to the Lynch Rogues Gallery. Admittedly, it’s a more subdued film in many ways than its predecessor, but it’s sense of external spaces as internal spaces is pronounced. Whatever goes on “outside/in the world” mirrors the psychic turmoil or calm each character experiences. Harry Dean Stanton shows up as Ladd’s former squeeze and the gumshoe tasked with finding and retrieving Lulu, but it’s very much a picaresque and where the psychosexual tensions and acting out in Blue Velvet were jarring and challenging for some, there’s much in Wild at Heart that is tender and sensual, and almost life affirming.

Following soon after, Twin Peaks aired on ABC and that first season remains among the greatest examples of what can be done with the medium. It’s remarkable that it got the go-ahead. It lost its way in the second season, but returned to full power with the return of Lynch and Frost to the show. The world of Twin Peaks opened up Lunch’s vision to millions of people and it’s here that we being to see him accepted - more or less - into the mainstream. However, so much more is happening in this series than audiences at the time got. It wasn’t just a JJ Abrams style puzzle box; it was, like Eraserhead, like Blue Velvet, an incantation, a summoning up of forces outside the text and outside the tube.

Twin Peaks demanded your attention. There was no way to just have it on in the background while you vacuumed, though I bet Lynch would approve. Especially if you wore curlers and had a cigarette dangling from your lips. Extra credit if you’re a cis man. All of that said, Twin Peaks, like Lumberton before it, houses something dark, something evil, but here, it has a lineage stretching far back into time. Doesn’t it always, though?

The film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me was panned when it came out. A pity, because it is brilliant. It deepens out experience of the series and renders Laura Palmer more of a genuine person. In the Red Room we meet the past and sense the future, in the Black Lodge, we meet all the darkness we can stand. And then, there’s Bob (or BOB), Lynch’s supreme incarnation of pervasive evil, a darkness that seeps in like stagnant water in a swamp, the stench gets you first, then what’s ih the water. Twin Peaks: the Return closes the circle and bends the mind even more than the previous two seasons.

After Twin Peaks’ run and the cool response to the film, Lynch graded us with Lost Highway, which gave us parallel realities and alternative ontologies the likes of which we’d not seen before. Bill Pullman begins as one character that, thrown in jail, wakes up as Balthatzar Getty as another version of the same person or two different people sharing the same experience. This is the only time when Lynch suffers from overstuffing the film with narrative. Even so, he keeps the ideas coming and some staggering set pieces (Robert Blake’s Mystery Man at the party is genuinely unnerving, Rober Loggia beating the crap out of a motorist in a fit of road rage, are two examples.

What’s strangest is what Lynch did next. The Straight Story is a G-rated, uplifting story of Alvin Straight, played by the great Richard Farnsworth, who travels by tractor to visit his estranged brother (Harry Dean Stanton( after having a health scare. It’s an uplifting intimate saga of a road trip populated with wanderers and outcasts and presenting with a more wholesome vision of humanity than we’d ever seen before in his work, the cinematography, courtesy of Freddie Francis (his last collaboration with Lynch whom he first worked with on The Elephant Man and his last film before he passed away) is vast and expansive, full of saturated colors redolent with almost a kind of radiance in natural lighting and close shots that give the actors’ faces an expanse equal to the spaces outside.

And goddammit, it is a heartwarming story. Mary Sweeney’s (with John Roach) is a work of economy and rich humanity. She was also one of Lynch’s closest collaborators having begun with him as editor on Twin Peaks and continuing through Mulholland Drive in that capacity and as producer through Inland Empire.

Lynch began the twenty-first century with what many consider his masterpiece. Mulholland Drive introduced us to Naomi Watts as Betty/Diane and Laura Harring as Rita/Camilla as two women whose twinnings overlap and morph in an examination of identity and memory. We tread and in and out of spaces that seem to exist side by side as alternative dimensions on either side of a membrane. Betty is a young, bright-eyed actress; Rita is a dark-haired victim of an accident. It’s almost as if Shelynn Fenn’s character back in Wild at Heart had survived. There are golden tones and amber lighting for sequences that evoke a kind of somnambulant atmosphere juxtaposed with other scenes that pulse with light and color, as if our quotidian reality is too vivid. But we are still in a dream state. Is that a demon behind the dumpster and whence the Winkies? But it is the overarching atmosphere that draws us in and renders us drugged into an oneiric world that only feels like ours. Or more tellingly, that ours is a simulacrum of.

Lynch’s last cinematic feature is Inland Empire, a final tour de force that utilizes video in a way that alienated audiences, but I find glorious. Laura Dern turns in a career best performance as an actress who melds with or into the woman she’s portraying and as with Mulholland Drive, the lines between realities blur. Its glacial pace gives us time to linger over so much and the constructed world of film (and sit-coms; the short film Rabbits comprises a segment within the film) merges with the world we construct. As a final feature, ti’s a worthy close to a great cinematic career.

Of course, we’re not done. Lynch continued shooting shorts, music videos, a documentary on meditation , and a concert doc of Duran Duran. Then there’s Twin Peaks: the Return. It’s a fitting capper to his career. It might also be his finest work. I’ve written about it elsewhere and nothing here is intended to be exhaustive or more than random thoughts that occurred to me as I strolled down memory lane.

More important is what David Lynch meant to us. For us artists and weirdos, voices like his are guideposts for what’s possible, for new ways of seeing the world or worlds around us and in us. The adjective “Lynchian” has entered the lexicon, but is often as flaccid as “surreal” and as overused and sometimes rendered devoid of meaning because of that overuse.

That said, you know Lynchian when you see it. You see it in a lot of films that self-consciously try to imitate the master, but you also see it in his contemporaries. I’d argue parts of Scorseses’s Cape Fear are Lynchian, as well as Shutter Island. Stone’s U-Turn has flourishes that wouldn’t be out of place in a Lynch film. However, only Lynch could do Lynch.

I don’t like analyzing his films because I think that’s too much like treating them like puzzles to be solved and like dreams, that’s not what they’re for. Analysis is death to these works; they live and breathe in our collective and individual unconsciousnesses.

No, as with Cocteau, Terry Malick, Tarkovsky and a few others, approach Lynch’s works like poems, like dreams.

“In dreams I walk with you

In dreams I talk to you

In dreams you’re mine all of the time

We’re together in dreams, in dreams.”

from “In Dreams” by Roy Orbison, for obvious reasons

Comments

Post a Comment